Can Europe Survive? That Depends on France

Will France need to be bailed out under the latest of the European Central Bank’s (ECB) damage limitation devices, the magically named Transmission Protection Instrument? France’s minority government under embattled Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu has finally succeeded in passing a social security budget—by including a provision temporarily suspending President Emmanuel Macron’s flagship pension reform—but negotiations will now begin on Friday on a draft state budget bill, which needs to pass by the deadline of December 31.

A fiscal collision between France and Germany, the two biggest economies in the euro area, looks well-nigh inevitable in the next 18 months. France is preparing for a presidential election in (or before) April 2027 that could well bring a far-right leader into the Elysée Palace. This would represent a grave test for cohesion between France and Germany, a partnership that has been a cornerstone of European integration for 70 years.

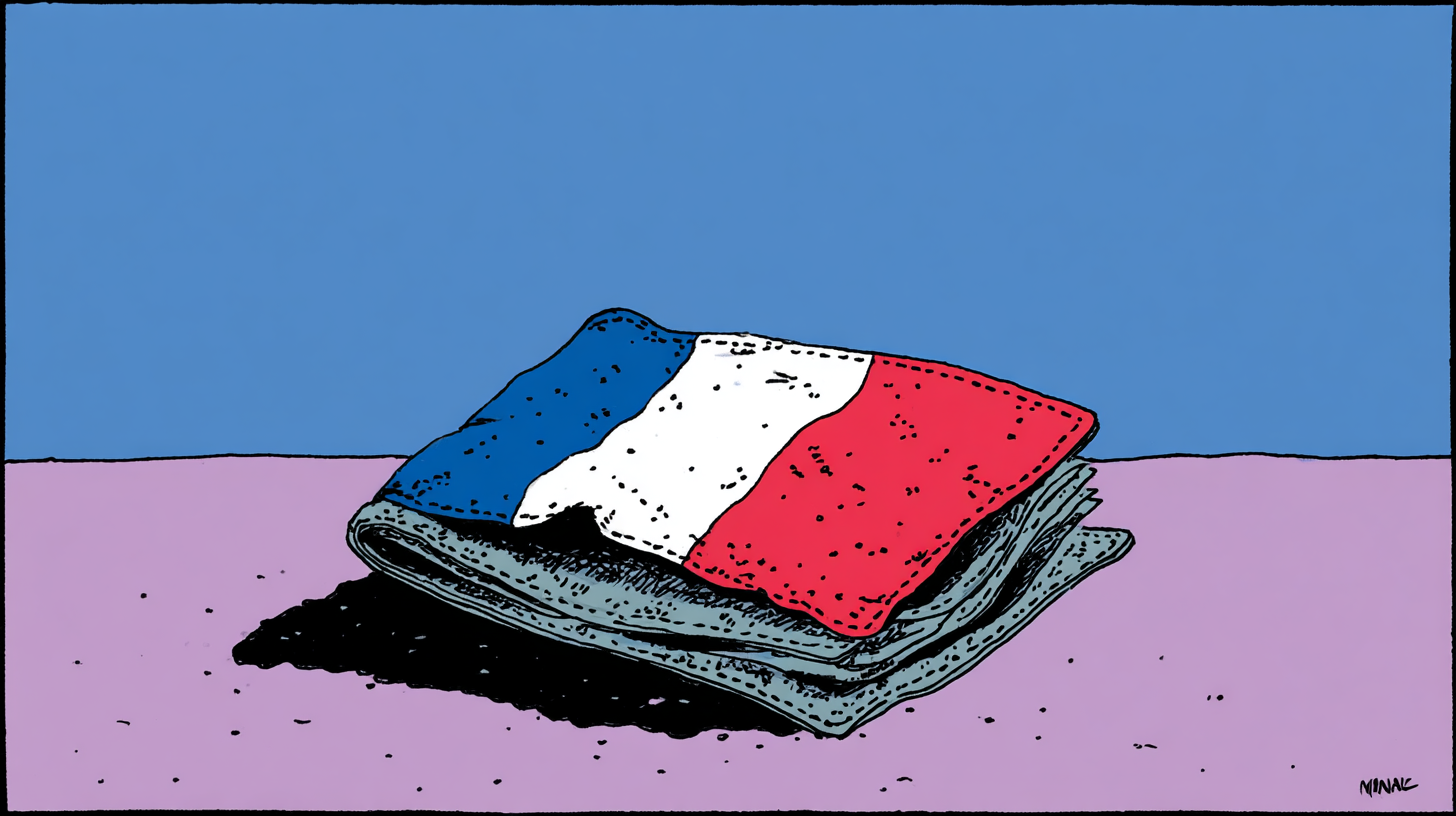

The French budget deficit appears out of control: at over 5% of GDP, it is well above the European Union benchmark of 3%. The yield on French government bonds, once considered the safest in the euro area after German Bund issues, has risen to above Italian and Greek levels, showing the extent to which France has fallen out of favour with worldwide investors. France’s budgetary malaise confirms my view, set out in my new book Can Europe Survive?, that the country is adding potently to the continent’s myriad fault lines.

The single most damning indicator of insidious Franco–German strains concerns divergences over public debt. The French have been profligate while Germany has practised fiscal orthodoxy. The two countries’ debt-to-GDP ratios were virtually identical in 2007, just before the global financial crisis, but France’s has nearly doubled since then while Germany’s (after rising in subsequent years and then falling back) has remained unchanged.

When the ECB invented the Transmission Protection Instrument, known as TPI for short, in July 2022, its acronym was said in some circles to stand for “To Protect Italy.” Many observers believed the ECB’s new, conditional (and so far unused) mechanism for purchasing government bonds was conceived above all to prop up the finances of the nation with the highest public debt in Europe. But according to the elder statesman of European finance, Niels Thygesen, the 90-year-old Danish economics professor who for eight years was chairman of the European Fiscal Board monitoring European public sector finances, “France has replaced Italy as the major problem country within the euro area.”

The TPI lays down a route for the ECB to start a programme of government bond purchases for countries facing an “unwarranted” rise in interest rates on capital markets. The instrument represents a potential lifeline to help troubled countries within Europe’s single-currency system overcome the punishment of destabilising higher interest rates. That penalty lies in store if euro bloc member countries persistently fail to curb budget deficits. Unfortunately, France, over the past decade, offers a near-permanent example of blatant disregard for the “stability first” rules of economic and monetary union (EMU). Ever since President Emmanuel Macron took the ill-conceived step of dissolving parliament and calling early legislative elections in June 2024, a fractious National Assembly has been beset by squabbles over raising taxes and cutting spending to try to align the country with European stability guidelines.

The latest contretemps has arisen because of a Socialist party threat to bring down Lecornu’s fragile government if he does not agree to levy higher taxes on the country’s wealthiest in the 2026 budget. Unless the government gives in to its demands, Olivier Faure, the leader of the party, which holds a swing vote in the hung parliament, has threatened to call a no confidence vote—possibly presaging a further round of parliamentary elections. A further parliamentary tug of war could even precipitate a premature presidential contest, ahead of the scheduled 2027 polling date at which Macron will be stepping down after two five-year terms.

The TPI is part of an elaborate manoeuvre to shield higher-debt countries from the consequence of rising higher European interest rates, necessary to counter an inflationary surge following the ending the Covid pandemic and the start of the Russo–Ukrainian War. However the mechanism is intended to take effect through selective ECB bond buying only if the “spreads”—the interest rate difference between higher and lower ranking bonds within the euro bloc—widen in a way that the ECB governing council judges is not justified by economic fundamentals.

The problem for French politicians is that ECB policy-makers, in informal soundings over the past few months, have concluded that the recent rise in French spreads has been largely self-induced and is not the result of unfair speculation. Of crucial significance, Joachim Nagel and François Villeroy de Galhau, governors of the Bundesbank and Banque de France, who have built close ties during the past three years, would be expected to state jointly the overriding necessity to maintain EMU’s stability-orientated policies. Consequently, if any French government, on the basis of present realities, were to call for activation of the TPI, the ECB would almost certainly reject the request. A rebuff would subject European decision-making to unforgiving scrutiny and would probably unleash a political and financial crisis. For all these reasons, attempted recourse to the TPI appears highly unlikely in the near future.

Central to the French imbroglio is the wealth tax named after the economist Gabriel Zucman. The French Left has long favoured such a tax, in the teeth of resistance from Macron, his centrist allies and right-wing parties, who say it would trigger capital flight, depress investment and constrain efforts to modernise and reform the economy.

Lecornu’s agreement to suspending Macron’s pensions reforms was a concession to the Socialists that allowed his government to survive two no-confidence votes earlier in October. However, the budget talks have become particularly complex after Lecornu also promised not to use a constitutional tool that allows the budget to be adopted without parliamentary debates. This has opened up all budget areas to parliamentary negotiations.

The Franco–German alliance within the European Community (from the 1990s, the Union) has often featured dissent and conflict—testified by much discord between Paris and Berlin about preparations for the euro in 1999 as well as, more recently, by disagreement on nuclear energy, trade agreements with Latin America and joint activities to build fighter aircraft. The spectre of a possible shift to the extreme Right in Paris now looms large.

The appearance in the Elysée of a leading figure from Marine Le Pen’s far-right Rassemblement National (RN) party—either Le Pen herself or (should she be impeded by her five-year ban from running for office, against which she is appealing) the RN president Jordan Bardella—would bring strain but not necessarily breakdown to Franco–German relations. My view is that a shift to the Right in France might even be salutary for Friedrich Merz, Germany’s centre-right Christian Democrat chancellor since May 2025—who has already had to forge links with two failed French prime ministers during his brief time in office. In my opinion Merz would get on reasonably well with a far-right figure in the Elysée.

Merz is a hard-headed politician. His rationale is built around trying to withstand the rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), the far-right anti-euro and anti-immigration grouping in Germany which has become the second biggest parliamentary party. He has inaugurated a much tougher policy on migrants, building on border control ideas suggested 10 years ago to previous Christian Democrat chancellor Angela Merkel, which she rejected on both legal and moral-political grounds. Merz’s policies on immigration, and his steely demeanour on law and order and discipline in state finances, have some appeal to voters on the Right who feel disenfranchised by mainstream parties, including the Social Democratic Party with which Merz is in fragile, low-majority coalition. This could slow or even reverse the meteoric ascent of the AfD. Another factor that could hearten Merz is the setback in the Netherlands’ election on October 29 of the Freedom party of anti-immigration populist Geert Wilders, whose coalition government collapsed in June—a landmark that heralded a move back to the Dutch political centre.

Against a rocky German economic background—growth is still stalling badly, extending six years of stagnation—Merz has won support from a steady approach to foreign policy. But the domestic picture remains disquieting. Large-scale fiscal expansion for defence and infrastructure agreed at the outset of his chancellorship is taking far too long to work through. Merz famously promised an “autumn of reforms”—but so far little of note has materialised.

On the European front, Merz has healed some previous fractures with France in the symbolic area of nuclear energy, assembled a working relationship with Donald Trump in the White House, produced leadership over Germany’s backing for Ukraine over the war with Russia, and forged a much-needed link with the UK in economics, trade and defence. This might, if Merz is lucky, strengthen his credentials as a seasoned business-orientated political operator who can do business with a range of awkward foreign leaders.

The barriers towards electing AfD head Alice Weidel as the next German chancellor remain much higher than those facing an RN leader. A combination of a right-of-centre chancellor in Berlin and a far-right president in Paris might even emerge as a relatively stabilising force. The key would be whether they can agree a constructive European economic policy that puts growth firmly back on to the agenda.

Here there is no shortage of recipes for improvement—but collective inability to put them into effect. Mario Draghi, the former Italian Prime Minister and ECB president, presided over a learned series of recommendations for improving European competitiveness in a well-publicised report for the European Commission in September 2024. In a speech on October 24 in Spain, Draghi was at his most plaintive. “Why can’t we change?” he asked. “How serious must a crisis become for our leaders to join forces and find the political will to act?”

Draghi is pleading for a simplification of European procedures under a new, pragmatic federalism. Merz and many other conservatives and centrists would call for much more far-reaching deregulation. But unless France and Germany can join together to pursue policies that actually work, such recommendations are unlikely to bear fruit—and Europe will slip still further behind in the increasingly ruthless competition with China and the US.

Can Europe Survive? is published by Yale University Press.

This article originally appeared at CapX.

The post Can Europe Survive? That Depends on France was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.