Sovereign Wealth Funds and the West

When I was at school, learning about the privatization waves of the 1980s under Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, my teacher made a comparison between our own fortunes in Britain, and those of our North Sea neighbors in Norway, that stuck with me.

In Britain, we used the proceeds from re-privatizing key industries like British Petroleum to fund the tax cuts that were considered necessary to revitalize the economy. The story is well-told: by liberalizing the economy, the initial shortfall in direct income would be offset in the short-term and exceeded in the long-term from the proceeds of an energetic private sector, and a free-market economy would provide the future prosperity, built on a broad and reliable tax base, necessary to keep Britain afloat.

In Norway, on the other hand, such future prosperity was secured in a different way: through a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF). As the website for the Norwegian investment bank (set up as part of this fund) explains, the discovery of oil in the Norwegian North Sea in 1969 that funded a rapid economic explosion led to the establishment of (what is now) the Government Pension Fund Global in 1990. All proceeds from the sale of the oil would hereafter be used to fund investments in global opportunities.

There is a particularly telling paragraph on the website:

Oil revenue has been very important for Norway, but one day the oil will run out. The aim of the fund is to ensure that we use this money responsibly, think long-term and so safeguard the future of the Norwegian economy.

The Norwegian SWF is now the largest in the world, with over $1.78 trillion in Assets Under Management (AUM).

Should Britain have done the same? One could easily say, “One day the revenues from privatization will run out.” Perhaps Britain should have set up its own SWF, but spilt milk and all that.

Nevertheless, Norway was not the first country to establish an SWF; in fact, as a recent article in Foreign Policy on sovereign wealth funds and instrumental capital explained, that title goes to Kuwait, in 1953. The Kuwait Investment Board, now the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA), was set up to manage (you guessed it!) the country’s surplus from oil reserves. The KIA is currently the fifth-largest SWF in the world, at $1 trillion in AUM, despite Kuwait being a very middle-ranked economy. Following Kuwait’s example, many Gulf States established their own SWFs, banking the revenue that the sale of oil generated, and using it to modernize their nations.

But the role that SWFs play is changing, and this is partly a consequence of a subtle reimagining around the world of the role of the State in politics. Part of the vision of the liberalization of economies in the late 20th century was the “rediscovery” of the State as a neutral arbiter and regulator of the autonomous spheres of life—civil society, personal preference, religious liberty, and (of course) the market. SWFs were an attractive counterweight to the instability that may have accompanied such liberalization; by providing a long-term source of wealth for the sovereign body politic, the State could be somewhat insulated from the spontaneity of civil life.

Jared Cohen and George Lee, the authors of the Foreign Policy essay (and co-heads of the Goldman Sachs Global Institute), argue that SWFs have, paradoxically, dragged the State back in as an economic actor in its own right. Because of the sheer size of the Funds (in total the 170 SWFs around the world have $14 trillion in AUM), States are now able to leverage these resources to pursue their own ends, deploying capital to advance their strategic national objectives.

The Middle East continues to be the epicenter, the fulcrum on which this lever moves. Collectively, Middle Eastern SWFs (such as Kuwait’s, Saudi Arabia’s, Bahrain’s, and Qatar’s) have $5.6 trillion in AUM, and are projected to reach $8.8 trillion by 2030. If this was a single nation, as Cohen and Lee write, it would be the third-largest economy in the world. And each of these nations are, in their own way, pursuing a similar goal, not unlike that of Norway’s: diversification.

One day, the oil will run out, so these petroeconomies must use the enormous SWFs they command to help prepare. But as a result, it is forcing the Gulf States to think and act more strategically about who they are partnering with, because these comparatively small nations are now competing with the largest economies in the world, China and the US: for example, Qatar has financed the construction of the US-operated Al Udeid Air Base, and has recently won the rights to “build a new Qatari Emiri Air Force facility in Idaho.”

Now the West is racing to catch up. Britain does not yet have an SWF in its strict sense, in part because of our complex constitution, but the newly-elected government in 2024 did establish a “National Wealth Fund” (NWF). While the NWF is likely to operate in the same way as an SWF, it is not funded in the same way: “Rather, the NWF is financed by taxation and borrowing, which means its investments are likely to attract public, political and media scrutiny.”

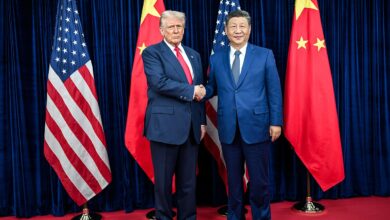

Meanwhile, the United States is setting up its own SWF, spurred on by an executive order signed by President Trump in February. The US constitution plays its own complicating role here, as many States are empowered to have their own versions of SWFs, known as “Permanent Funds.” Texas, for example, has a Permanent Education Fund (AUM $55.6 billion) and a Permanent University Fund (AUM $31.8 billion).

Regardless, the US SWF looks set to be exactly what Cohen and Lee describe as “instrumental capital,” as instead of investing directly into assets, the US SWF, under President Trump at least, is likely to act as what the think tank OMFIF called “a powerful ‘crowd in’ catalyst for public-private investment partnership.” In other words, where confidence in promising and emerging opportunities is low, the support of the US SWF will buttress investors’ faith and keep them from pulling out. Case in point: Stargate, the AI venture, may be “struggling to get off the ground… because scepticism among investors remains high,” but with the “addition of long-term US SWF investment,” risk is considered to be reduced, “making it attractive to private capital for co-investments.”

But is the West too late to the party? Some may say better late than never, and given the timeliness of the US fund’s creation amidst the AI explosion, this could well prove to be true. Moreover, the role of SWFs seems to be shifting from acting independently of the specific government in place—they are, after all, sovereign wealth funds—and instead being used as tools of the geopolitical strategy of whichever government holds the reins.

Whatever the future of SWFs, they certainly are no longer passive presences in the global economy; they are actively shaping it.

The post Sovereign Wealth Funds and the West was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.