Centenarians for Liberty

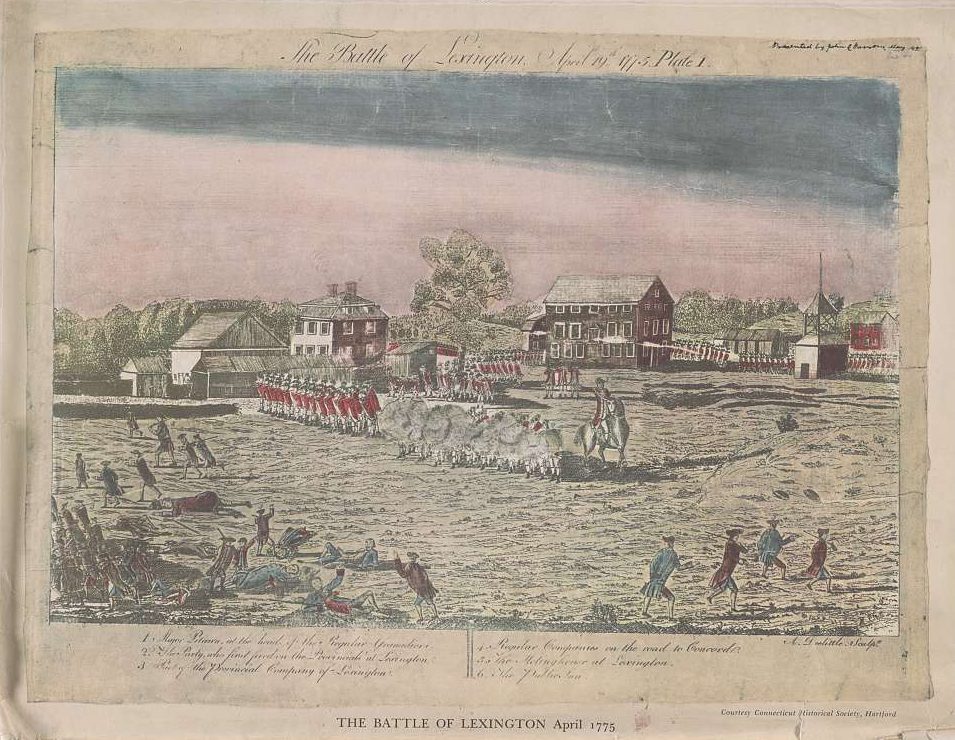

On the morning of April 19, 1775, British troops marched into Lexington, Massachusetts, on their way to confiscate weapons in the nearby town of Concord and to apprehend the colonial firebrands Samuel Adams and John Hancock. When a shot was fired—no one knows by whom—a skirmish erupted. As the smoke cleared, eight American patriots were dead. The American Revolution had begun. It was 250 years ago today.

Eighty-nine years later, as another war was nearing its end, only seven veterans of the Revolution were still alive. Ranging in age from 101 to 106, they had been teenagers when they took up arms against Britain.

Suppose you had been alive in 1864 when those seven veterans still lived. Wouldn’t it be a thrill to visit each of them, take a photo or two, and pry loose their memories of those momentous days so long before?!

Reverend E. B. Hillard set out to meet all of the men in the summer of that last full year of the Civil War. He reached six of them at their homes in New York, Maine, and Ohio. The seventh, in Missouri, was beyond his reach. He interviewed five of the six (one was too ill to speak), took a photo of each man and his house, and then wrote a remarkable book titled The Last Men of the Revolution. I recently bought a 2013 facsimile reproduction of it—bound in genuine goat leather, no less—but for a few bucks less you can get an inexpensive copy on Amazon.

Hillard fully understood the historical significance of his project, as his Introduction reveals:

The present is the last generation that will be connected by living link with the great period in which our national independence was achieved. Our own are the last eyes that will look on men who looked on Washington; our ears the last that will hear the living voices of those who heard his words. Henceforth the American Revolution will be known among men by the silent record of history alone.

The first of the six Hillard met and profiled in the book was 102-year-old Samuel Downing of Edinburgh, New York. He was living in the house he built some 70 years before, and everybody for miles around knew exactly who he was. They regarded him with “respect and affection.” Only the day before, the old man had walked five miles (round trip) to a shoemaker’s shop to have his boots spiffed up. Of the six surviving veterans, Hillard says Downing was “the most vigorous in body and mind.” The Reverend writes:

Indeed, judging from his bearing and conversation, you would not take him to be over seventy years of age…[H]e is strong, hearty, enthusiastic, cheery: the most sociable of men and the very best of company. He eats his full meal, rests well at night, labors upon the farm, hoes corn and potatoes, and works just as well as anybody. His voice is strong and clear, his mind unclouded, and he seems, as one of his neighbors said of him, “as good for ten years longer as he ever was.”

Not bad in 1864 for someone born in 1761!

Source: Library of Congress

Downing regaled Hillard with stories the Reverend found riveting. Downing’s first duty in the war was “to guard wagons from Exeter to Springfield.” He and fellow patriots once ambushed British carriages transporting rum and enjoyed a good party that night.

The old man knew the infamous Benedict Arnold and served under him in the Mohawk Valley before Arnold turned traitor. “A stern-looking man but kind to his soldiers,” said Downing, but “he ought to have been true” to the American cause.

From “right opposite Washington’s headquarters,” Downing watched Lafayette prepare the ground just before the pivotal Battle of Yorktown. Of Washington, Downing said, “I saw him every day.” Hillard inquired, “Was he [Washington] as fine a looking man as he is reported to have been?” Downing replied in the affirmative, adding, “But you never got a smile out of him. He was a nice man. We loved him. They [the troops] would sell their lives for him.”

Downing recalled, “When peace was declared, we burnt thirteen candles in every hut, one for each State.” After their “delightful” conversation, Hillard departed, his heart “swelled afresh with gratitude to the men who had rescued their land from the tyrant.”

Rev. Hillard’s next stop was Syracuse, New York, to see a veteran named Daniel Waldo, just two months shy of his 102nd birthday. Sadly, because of a fall just days before, Waldo lay mostly unconscious on his deathbed. “To see him, even without knowing him, was to love him,” wrote Hillard.

Despite the situation, Hillard assembled a fascinating profile of Waldo from friends and family and the many articles written about the man when he was in better shape. Waldo had been a preacher who commanded immense adoration. Hillard quotes a close friend of Waldo’s, who said, “At the close of a life of more than a hundred years, there is no passage in his history which those who loved him would wish to have erased.”

The stories revealed to Hillard by the remaining four—Lemuel Cook, Alexander Milliner, William Hutchings, and Adam Link—are all poignant and memorable. I couldn’t help but wonder if God granted these men long lives so they could reveal to E. B. Hillard how blessed the country was to have them. I hope you’ll want to pick up a copy of the book and read about them for yourself.

I don’t know about you, but I would give anything to spend even a moment with centenarians who fought for America’s liberty. Thank you, Rev. E. B. Hillard, for doing that very thing so long ago.

Additional Reading:

The Last Men of the Revolution by E. B. Hillard

The Revolution’s Last Men: The Soldiers Behind the Photographs by Don N. Hagist

‘Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death,’ 250 Years Later by Lawrence W. Reed

Get Ready for 2026! by Lawrence W. Reed

Remembering the Ides of March (in 1783) by Lawrence W. Reed

How Sound Money Won the Battle of Yorktown—and Saved the American Revolution by Lawrence W. Reed

The post Centenarians for Liberty was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.