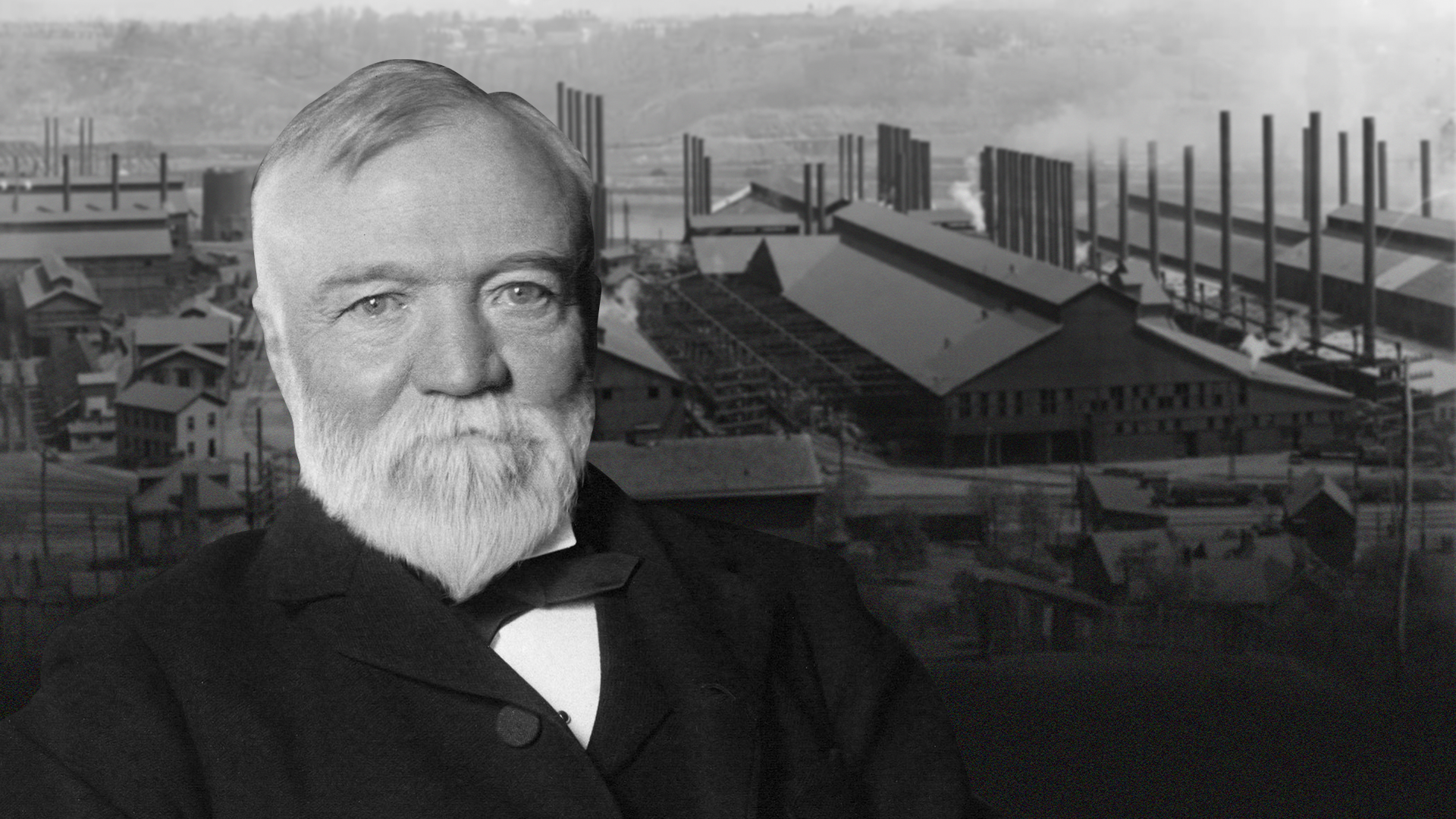

Andrew Carnegie: A Hero of Capitalism

Andrew Carnegie’s life, if conceived by an imaginative novelist, would be difficult to believe. It is perhaps the greatest example of an individual rising from “rags to riches” via talent and productive effort, a rise enabled by the essentially free market system of 19th-century America.

Early Life

Parts of his biography are well-known but bear repetition: He was born in 1835, emigrated with his poverty-stricken family from Scotland to the Pittsburgh area at twelve, and at thirteen was working in a factory for $1.20 per week. Much of Carnegie’s early career was spent working for the Pennsylvania Railroad. Despite having received only five years of formal schooling, he was a quick learner and possessed a burning ambition to succeed. As Louis Hacker writes, “He [quickly] became a telegraph messenger boy; at 15 a telegraph operator; and at eighteen, the confidential clerk of Thomas Scott,” who ran the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Western Division.

The young Carnegie was brilliantly entrepreneurial: He recognized the virtue of T.T. Woodruff’s innovation of sleeping cars on trains and invested in Woodruff’s company. In 1859, Carnegie saw the possibilities of the oil production just beginning in Western Pennsylvania, invested in an oil business, and made a fortune. After the Civil War, he realized that railroads were poised to sweep across the vast American West. He founded companies to produce iron rails and construct iron bridges to span the continent’s mighty rivers; he proudly and accurately proclaimed the superior safety of iron to wooden bridges.

But by the early 1870s, he became convinced that Henry Bessemer’s innovative method of producing steel was the future. Often over objections from his own partners, he tore down his iron foundries and built steel mills, marking a pivotal moment in how Carnegie changed the steel industry forever. Carnegie was a genius at discovering and encouraging young talent, such as Henry Clay Frick and Charles Schwab, both of whom played key roles in the expansion of his Carnegie steel empire. “He was generous to his ‘associates’…seeking out talent everywhere and encouraging these younger men to become owners,” Hacker writes, “but he was always the master, the one who set policy and took the risks, expanding vertically and constantly growing, so that from 1880 to 1900 Carnegie dominated the steel industry.”

Revolutionizing the Steel Industry

Carnegie was a stickler for increasing efficiency and cutting costs, enabling him to substantially lower the price of steel. One of Carnegie’s methods enabling him to produce steel more efficiently than his competitors was the hiring of a chemist at his mills. The chemist showed Carnegie’s team how to scientifically distinguish superior iron ore from inferior ore and how to use waste products efficiently. These techniques, and others, enabled Carnegie to manufacture high-quality steel at lower cost. Historian Paul Johnson pointed out that America “was transformed into a republic by gentlemen politicians, but it was businessmen who made it, and its people, rich…He [Carnegie] supplied steel girders for the first genuine skyscraper, the Home Insurance Company in Chicago (1883)…He made steel for the Brooklyn Bridge, for the New York Elevated, and for the modern U.S. Navy…His furnaces produced nearly one-third of America’s output and they set the standards of quality and price.” Carnegie’s unbreached devotion to efficiency enabled his company to vastly lower prices of steel products. Consider, for example, that the price of steel rails declined from $160 per ton in 1875 to $17 a ton in 1898.

Think of the enormous benefits conferred on America by Carnegie’s productivity. Inexpensive steel was indispensable to the development of America’s distinctive contribution to architecture: the skyscraper. Apartment houses, office buildings, hospitals, schools, and so forth require large amounts of steel and would be prohibitively expensive absent its efficient manufacture. Similarly, Carnegie’s productivity made possible the great era of suspension bridges, including John Roebling’s masterpiece, the Brooklyn Bridge.

In a free market, innovations build on one another. At the turn of the 20th century, Henry Ford at the Ford Motor Company began to revolutionize personal transportation in the United States with the mass production of automobiles. These required large amounts of steel, and Ford’s ability to produce affordable cars depended on the efficiency in steel manufacturing perfected by Carnegie’s company. (John D. Rockefeller’s efficiency in producing inexpensive petroleum products at Standard Oil was similarly necessary for Ford’s success.) Further, such machinery as tractors, harvesters, and combines deployed by American farmers to grow huge amounts of crops requires substantial quantities of inexpensive steel.

Philanthropy and Legacy

In 1901, Andrew Carnegie sold Carnegie Steel to a conglomerate headed by financier J.P. Morgan for $303,450,000 (equal to roughly $11 billion in current value), making him the wealthiest man in the world. Leftist historians often deride Carnegie and other leading industrialists of the era as “robber barons,” as though their great wealth was fraudulently gained. But this claim ignores the fact that the personal wealth gained by Carnegie was a fraction of the immense wealth he created, either directly or via steel’s substantial contributions to other industries; a sum that is literally incalculable and which redounds to the immense material betterment of every man, woman, and child in the country. Paul Johnson was absolutely correct: It was businessmen who made Americans wealthy, not politicians. The capitalist system protects individual rights, thereby liberating entrepreneurs like Carnegie to produce; entrepreneurs who would be stifled under a socialist system in which business is controlled by the state, not by private individuals.

Carnegie represents the epitome of what was once an American ideal: the self-made man. In the late 19th century, American novelist Horatio Alger wrote boys’ books, most of which were variations on a single theme—that poor boys could grow up to have enormously successful careers based on honesty and hard work. Ragged Dick was the title of his best book; there were others in a similar vein. Many poor American youths were motivated by Alger’s books to take advantage of the freedom and upward mobility of America’s capitalist system, to work honestly and productively, and to rise into middle-class affluence or beyond.

Carnegie himself believed his example could be followed by others. He gave away in philanthropy an estimated $350 million, much of it funding colleges, libraries, and scholarships for poor, talented, ambitious, hard-working youths like he had been. But magnificent as this was, Carnegie’s greatest contribution to human life was the abundant supply of inexpensive steel that rolled endlessly from his mills, facilitating building of every type, first in America and then around the world.

But in the 20th century, leftist intellectuals rejected Alger’s stories as a form of capitalist myth-making. They scorned the tales of self-made men and rags-to-riches success stories as either fables or narratives of exploitation. Arthur Miller’s famous play, Death of a Salesman, is one example of such repudiation. But standing in formidable corroboration of Alger’s theme, and in sharp opposition to the anti-capitalist propaganda, is the towering, real-life story of Andrew Carnegie, the ultimate success story under the freedom of America’s capitalist system.

Additional Reading:

Charles Schwab and the Steel Industry by Burton W. Folsom

The Paradox of Carnegie Libraries by Chris Cardiff

The post Andrew Carnegie: A Hero of Capitalism was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.