Track Record

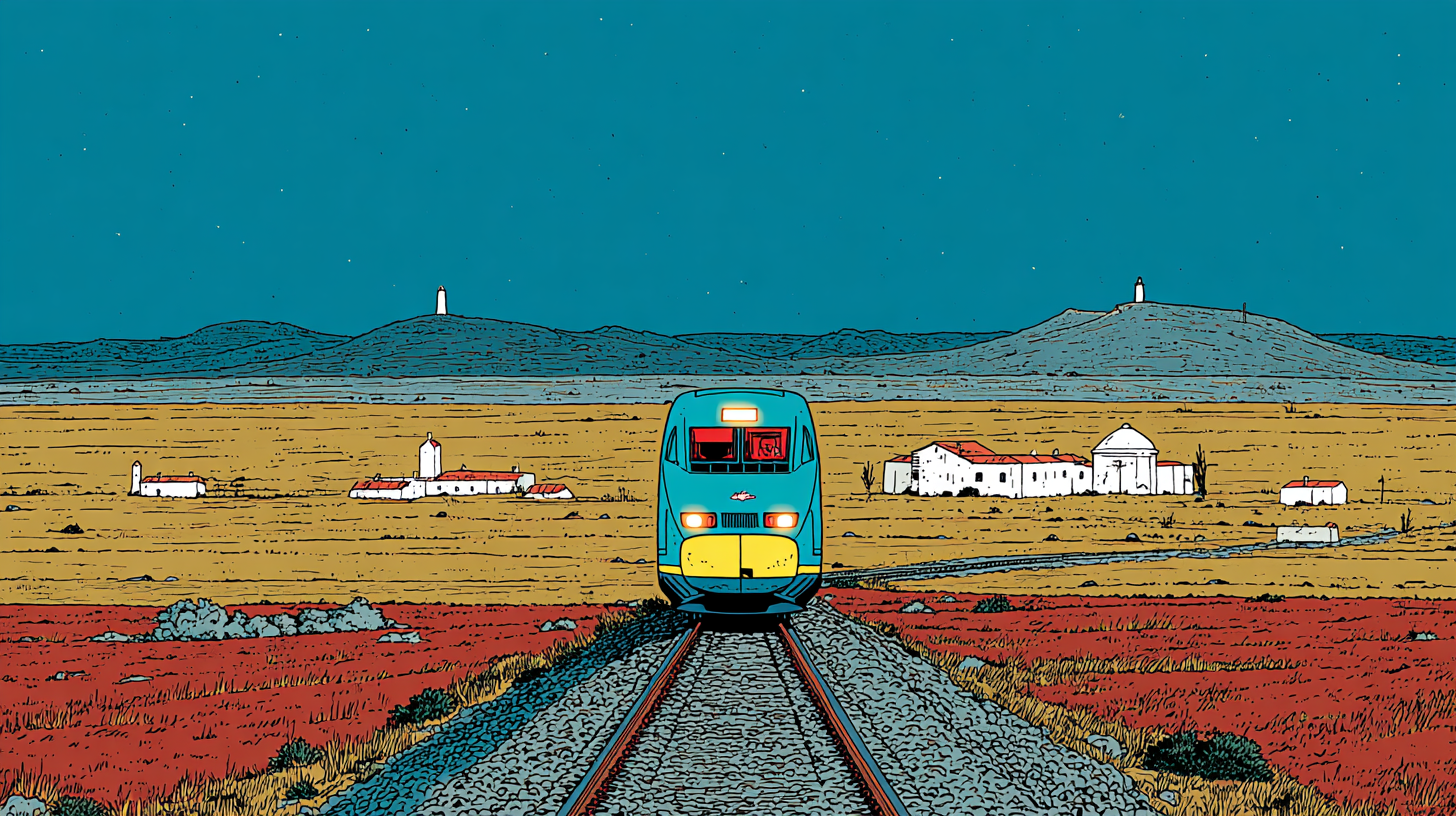

Spain receives much well-deserved praise for its rail network, the second-largest in the world after China’s, with around 4,000 kilometers (2,485 miles) of high-speed track. Rail travel in the Iberian country now accounts for 56% of all travel, more than road and air combined, with high-speed services connecting over fifty Spanish cities. In 2009, then-US President Barack Obama credited the 470-kilometer (292-mile) line linking Madrid to the southern city of Seville—the country’s first high-speed service, opened in 1992—as one of the inspirations for creating a network of comparable efficiency across America.

But after four incidents in less than a week, public trust in Spain’s world-class network has been shaken. The most serious accident occurred on the evening of January 18 near the southern town of Adamuz, when a train operated by Italian company Iryo derailed on its way north from Málaga to Madrid, veering onto the opposite track. About twenty seconds later, a train operated by state-owned Renfe, traveling south from Madrid to Huelva, slammed into the derailed carriages at 200kph (124 mph). The collision killed 46 people and injured almost 300 others, 15 critically. This was followed two days later by an accident outside Barcelona, in which a commuter train collided with a collapsed wall, killing the driver and injuring 37 others; the same day, another train near the Catalan capital hit a rock, but there were no injuries. Two days after that, several people received minor injuries near the southeastern city of Cartagena, when a crane swung into the windows of a passing commuter service.

Spain’s Socialist-led government has promised to uncover the truth about the Adamuz tragedy, and pay €20 million ($24 million) in compensation to its victims—but that won’t answer their questions about what caused it. Speaking at a state funeral held for the deceased in Huelva on January 29 (attended by Spain’s king and queen, but not its Socialist prime minister Pedro Sánchez), Liliana Sáenz, who lost her mother in the collision, said: “Only the truth will help us heal this wound.”

Several clues have already been discovered. Spain’s Railway Accident Investigation Commission found marks on the wheels of the derailed Iryo carriages that might have been caused by a broken weld in the track near Adamuz. It also found similar grooves on trains that passed over that section earlier on January 18, indicating that it was fractured before the crash—not, as some speculated, as a result of it. The Spanish train drivers’ union SEMAF sent a letter to the state railway operator Adif last August, warning of damage on several lines, including the Adamuz stretch. SEMAF has called a three-day strike for February, in protest of what it describes as “the constant deterioration of the rail network.”

Meanwhile, the Conservative People’s Party (PP) has seized on the Adamuz crash as an opportunity for revenge. More than 230 people died in the catastrophic floods of October 2024, most of them in Conservative-controlled Valencia. The region’s then-president, Carlos Mazón, was heavily criticized for his handling of the disaster, eventually resigning. Now, it’s payback time. The Valencian administration has criticized what it sees as disproportionate aid given to the Adamuz victims. According to spokesperson Miguel Barrachina, victims of the floods “received about €72,000 [each] compared to €210,000 for the victims of the train accident.” “For Sánchez,” he concluded, “a Valencia victim is worth a third of any other victim.”

The PP’s national leader Alberto Núñez Feijóo has called for Sánchez to appear before a Senate committee, and for the resignation of Transport Minister Oscar Puente. “The state of [Spain’s] railways,” he said, “is a reflection of the state of the country,” a symptom of the Socialist-led government’s “collapse.” Isabel Ayuso, the PP’s influential president of Madrid, wants both Puente and Sánchez gone; while Vox says that the crash is proof of the government’s “criminal incompetence.” Surprisingly, Andalucia’s PP president Juan Moreno has not joined in the fierce attack on Sánchez’s government.

Feijóo’s words, however, have rebounded against him. He was president of the northwestern region of Galica in 2013, when 79 people were killed in a train crash near Santiago de Compostela (Spain’s most recent rail catastrophe until a few weeks ago), and conversations on social media are dredging up some uncomfortable facts about the aftermath. In 2021, a platform for the victims demanded that Feijóo respond to accusations that he cut safety measures to streamline construction of the high-speed track. (The allegations came from then-Transport Minister José Ábalos, who’s now in jail, suspected of fraud.) Most embarrassingly, Feijóo said at the time that he wouldn’t use victims’ pain for political gain. Five years on, such scruples seem to have deserted him.

Puente, meanwhile, is living up to his nickname of “Sánchez’s Rottweiler.” During a heated parliamentary session on January 29, in which PP ministers shouted at him to resign, he claimed that Spain’s annual rail investment totaled around €5 billion in 2025, up from €1.7 billion in 2017 (when the PP was in power). Since then, the Transport Minister claimed, railway maintenance spending has increased by 66%. The section of track near Adamuz was renovated last May, as part of a €700 million refurbishment of the 34-year-old line connecting Andalucía with Madrid. But as Puente himself has clarified, that does not mean all of its components were replaced: the broken weld under investigation connected a new segment of track with a much older one.

Rail investment might have increased under Sánchez, but Spain is still spending more on new lines than repairing old ones. Of the annual average of €1.5 billion Madrid spent on high-speed infrastructure from 2018 (the year Sánchez took power) to 2022, only 16% was allocated for maintenance, compared to between 34% and 39% in France, Germany, and Italy. Between 2015 and 2024, reported problems with tracks, including breaks, rose from 440 to 716. One expert estimates that Spain needs to increase its maintenance spending from €11,000 per kilometer of track to €150,000.

As with the floods of 2024 and the freak blackout last April, the Adamuz train crash has revealed the extent of Spain’s political polarization—a situation in which politicians seize on any event, no matter how tragic, to score points against their opponents. As Liliana Sáenz, the woman who spoke at the state funeral, said: “[The 46 people who died] were part of a society so polarized that it began to crack a long time ago.” Those cracks are also in urgent need of repair.

The post Track Record was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.