China’s Global Reach

For China, the world’s second-largest economy, the past year’s economic fortunes have been characterized across three dimensions: declining domestic demand; increased tensions in the Pacific; and strategic repositioning in the Middle East. Each of these dimensions have combined to force China to re-evaluate its longstanding economic policies.

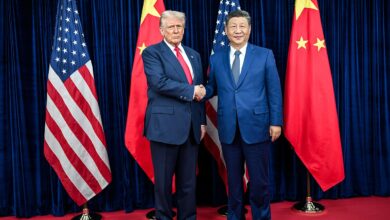

The ways in which China has come under pressure from, and responded to, the tariff policies of President Trump has led to some diagnoses of China as being on the verge of collapse due to a headline of slowing growth. In reality, the industrial nature of the nation remains high, be it industrial output, scale, or mobilization, allowing China to continue producing at an elevated level.

However, as Damian Ma and Lizzi Lee explained for Foreign Affairs, China’s role as the workshop of the world is under question as it attempts to balance its economy and encourage domestic demand in the face of declines at home. In fact, this appears to be a primary goal of Beijing’s leadership, who declared at the Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC) in December 2025 that “Task One of China’s 2026 economic work” is to “adhere to domestic demand as the main driver and build a strong domestic market.”

It is not only poor demand at home for the products of the nation’s factories that is damaging to the economic prospects of the country, but is now considered to be a security and strategic weakness. So much so that in the Chinese Communist Party’s own intellectual journal Quishi, President Xi Jinping argued in December that expanding domestic demand is “necessary for maintaining the long-term, sustained, and healthy development of my country’s economy, and also for meeting the people’s growing needs for a better life.”

As Lizzi Lee also wrote with Jing Qian for Foreign Policy, China’s economic model has been predicated on state-directed industrial investment kick-starting processes that lead to mass production, with domestic consumption as an eventual, but not targeted, outcome. This has meant that there is an imbalance in the Chinese economy with mass production leading to an over-supply, while low incomes and poor wage growth are leading to an under-demand. When this occurs in an economy with low growth in wages, tight household budgets, and limited surplus capital for companies to reinvest, it leads to a negative spiral of suppressed prices, an inability to hire workers, and even lower profits to reinvest. It’s no surprise, then, that “for the first time, the CEWC [in December] highlighted an income-raising plan for urban and rural residents.” It is a structural, and not a singular, phenomenon: the Chinese system remains extremely effective at producing capacity, but less effective at converting that capacity into broad household income gains and sustainable domestic consumption.

It is within this context of declining domestic demand that China has been forced to respond to Trump’s tariffs. Were the domestic economy resilient enough with rising household incomes or increasing capital, the tariffs might pose less of a threat, but as it stands, their impact was predicted to exacerbate this tension even further. Amelia Lester’s 2025 end-of-year roundup summarized neatly the global context: Trump’s tariff escalations created global disruption and uncertainty, and Beijing’s response was shaped by the assumption that volatility itself was part of the US negotiating posture. In this context, however, China has seen the opportunity to exploit the global volatility that comes with both the disruption of tariffs, and the seeming end of America’s interventionism (a view that the opening of 2026 has seemingly reversed, at least initially).

As a result, China has looked elsewhere for opportunities to offset its structural economic issues—and has found willing and waiting partners in the Middle East, principally in the Gulf States.

China’s engagement with the region is in no way new: over the past 25 years, China’s economic engagement with the Middle East has evolved from straightforward energy procurement into a broad, state-backed commercial presence. In the early 2000s, relations were dominated by long-term oil and gas supply deals, particularly with Saudi Arabia and Iran, designed to underpin China’s industrial growth. From the 2010s onward, as has been well-recorded, this deepened into infrastructure finance, construction, and logistics, especially under what has come to be known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), with Chinese firms building ports, industrial parks, power plants, and telecoms networks across the Gulf and Levant.

But while China has long been a major trading partner and energy customer for Middle Eastern states, the past year has seen economic engagement increasingly paired with, and buttressed by, diplomatic positioning, conflict mediation rhetoric, and an explicit ambition to shape the region’s political environment.

Official Chinese messaging published at the end of 2025 is particularly telling: it frames China not merely as a partner for mutually-prosperous development, but as a stabilizing force advocating dialogue, multilateralism, and political solutions to regional conflicts—an especially attractive offer for states in a period of what looks to be withdrawing US hegemony. The language marks a departure from earlier Chinese insistence on strict non-interference, replacing it with what Beijing presents as “constructive involvement” grounded in economic cooperation.

At the start of 2026, China’s Middle East policy was articulated around a simple but significant premise: development and security are inseparable. Chinese officials are increasingly arguing that economic stagnation, reconstruction delays, and uneven development are not secondary effects of conflict but core drivers of instability.

Rather than abandoning its economic focus, China has recast it as the foundation of peace itself. There is a clear merging of domestic and international rhetoric here: trade and economic prosperity is an essential component of security and stability, and not merely a route to development.

Central to this strategy has been the re-casting of the BRI as a geopolitical as well as economic framework. Not only this Initiative, but China has sought to embed further projects within a broader architecture of global initiatives, including its Global Development Initiative (GDI) and Global Security Initiative (GSI). As a region particularly unstable but increasingly prosperous, the Middle East offers an obvious testing ground for this integrated model, where development finance, political dialogue, and multilateral engagement reinforce one another.

The post China’s Global Reach was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.