Iberia and Brussels

On January 1, Spain and Portugal celebrated their 40-year anniversaries of joining the EU. In 1986, as both Iberian nations transitioned to democracy after decades of stifling dictatorship, membership of the European Economic Community (EEC), as it was then called, was seen as essential to modernizing their economies and integrating with the international community. And though Eurosceptic parties have recently gained prominence in both countries, in general Spain and Portugal remain strongly pro-European: 73% of Spaniards believe that joining the EU has been positive for Spain, rising to above 90% in the neighboring nation.

The leaders of both countries share this belief. Luis Montenegro, Portugal’s center-right prime minister, said that joining the EU in January 1986 “consolidated our democracy, opened up the economy, modernized the country, and projected us onto Europe and the world.” Spain’s Socialist prime minister Pedro Sánchez, who has described himself as a “militant pro-European,” was even more enthusiastic: the past four decades, he said, have been “the best days in [Spain’s] history… We have built a first-class welfare state. And we have become a tolerant, diverse, vibrant, and attractive country for the whole world.”

In the decade leading up to their accession to the EEC, both countries had endured political turmoil. Spain completed a difficult transition to democracy, after the death in 1975 of dictator Francisco Franco, who had ruled for almost 40 years. In Portugal, the Carnation Revolution of 1974 toppled the Estado Novo, an authoritarian regime established in 1933 by Antonio de Oliveira Salazar. The two dictators had bound their countries together by signing the so-called Iberian Pact in March 1939, a non-aggression agreement also designed to keep Spain and Portugal out of a future war between the UK and Germany.

For Portugal, joining the EEC was almost a formality—the final stage in a process of internationalization that had begun decades earlier. It had been one of the founding members of NATO in 1949 and of the OECD in 1960, when it also helped form the EU Free Trade Association. In 1972, Lisbon signed a free trade agreement with the EEC, removing almost all commercial barriers between itself and the rest of the bloc. From 1950 to Salazar’s death in 1970, during the so-called “Golden Age” of the Portuguese economy, GDP per capita had increased by almost 6% annually; but by 1986, growth had stalled, and Portugal was one of Europe’s least developed economies.

Neither was Spain entirely isolated during the long decades of dictatorship. In 1958, it became a member of the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (the predecessor to the OECD). That same year, it joined both the IMF and World Bank, both of which contributed to a period of rapid economic expansion now known as the “Spanish Miracle” (1959–74). But the oil crises of 1973 and 1979 hit Spain hard, resulting in high unemployment and inflation. Throughout the early 1980s, annual growth hovered around 1% of GDP. By 1986, Spain, like Portugal, was in an economic rut—and joining the EU was seen as the best way out.

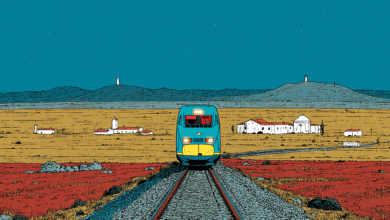

The economic benefits of EU membership for both Iberian nations have been substantial. Spain’s employed population has almost doubled over the last four decades, from 11 million to around 21 million. Its GDP has expanded by more than 100%, and it has received over €150 billion in EU funding, large amounts of which have been spent on developing its transport infrastructure (Spain’s rail system is now one of the best in Europe). Global exports of Spanish goods grew from €12.6 billion in 1986 (4.9% of GDP) to €141.5 billion in 2024 (8.9% of GDP). Spain’s economy is now the fastest-growing in Europe, and was named the best in the world in 2024 by The Economist magazine.

Portugal has followed a similar trajectory, although its recent growth hasn’t been as spectacular as Spain’s. Bolstered by over €160 billion in European funds, its GDP has expanded by 131% since 1986. Throughout the last two decades, the EU has funded more than 350 transport projects throughout Portugal, the most recent of which is to build a high-speed rail link between Madrid and Lisbon. Both Spain and Portugal have also benefited from being part of the Schengen Area, a border-free community of 29 European countries that enables the free movement of over 450 million people (which has also been a huge boost for tourism).

But EU membership hasn’t always been a blessing for the Iberian nations. Spain and Portugal were amongst the countries worst affected by the 2009 Eurozone debt crisis. The austerity measures enforced by the EU as conditions for bailouts caused economic hardship and mass unemployment, which in 2013 hit 27% in Spain and 17% in Portugal. Portuguese sovereign bonds were labeled “junk,” and nearly half a million people emigrated between 2011 and 2014, the biggest outflux in over 50 years. In Spain, unemployment rates, both amongst adults and 15–24-year-olds, are still high, as is the poverty level. Despite its stellar macroeconomic expansion and the massive public spending of its Socialist-led government, Spain remains one of the most unequal nations in Europe.

Brussels’s environmental policies are also proving unpopular within the farming industry. Throughout 2024, Spanish and Portuguese farmers participated in EU-wide tractor protests, expressing their frustration at higher regulatory costs, pesticide bans, and competition from cheap imports. In Brussels, demonstrators threw eggs, lit fireworks, and dumped manure outside the EU Parliament building. These demonstrations highlighted a persistent problem of EU membership: that centrally-imposed targets are not always in a nation’s or industry’s interests, and are more achievable for some countries than others.

Compliance with the EU’s green agenda has also been a condition of accessing funds through the “Next Generation” scheme, introduced in 2020 to help member states recover from the ruinous effects of lockdown. Here, too, Spain has come into conflict with the EU. Despite being one of the initiative’s biggest beneficiaries, with a total allocation of €140 billion, Madrid has been accused of opacity and lack of efficiency in handling its payouts. The EU is also investigating the possibility that Next Generation funds were misspent in connection with the Koldo corruption case, the protagonists of which were once amongst Sánchez’s most senior advisors.

Though generally pro-European nations, both Portugal and Spain have recently seen the rise of parties opposed to greater EU integration. Portugal’s Chega has modeled its slogan “God, country, family, and work” on Salazar’s “God, country, family,” and claims that Portugal should exit the EU if it ever tries to become a federal state; while Santiago Abascal, leader of Spain’s Vox, spoke out in 2021 against the bloc’s “federalist drift.” Chega and Vox are now the second and third most powerful parties in their respective parliaments—although their rise in popularity has been mainly owed to domestic policies, rather than their stance on Europe.

Opposition to centralized control from Brussels was, of course, one of the reasons for the UK’s decision to leave the EU in 2016’s “Brexit” referendum. But neither Spain nor Portugal looks likely to follow Britain’s example. For Madrid and Lisbon, the transformation of the past 40 years outweighs the dilution of sovereignty entailed by EU membership.

The post Iberia and Brussels was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.