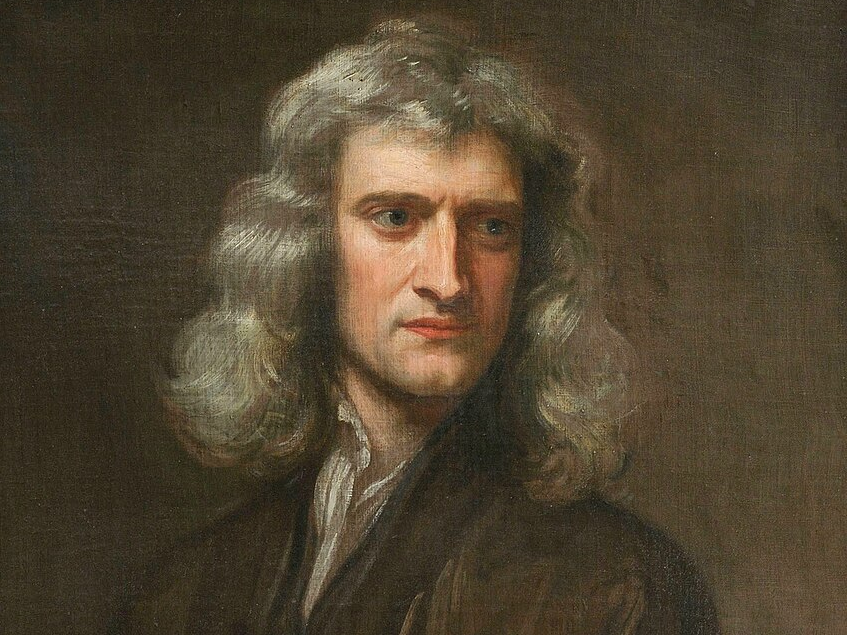

Anniversary of Isaac Newton’s Birth

On this day in 1643, in the village of Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth, Isaac Newton entered the world. Although to the people then, it wasn’t January 4—it was Christmas Day, 1642.

The great adjustment of dates that took place in 1752 changed calendars retrospectively—the shift from the Gregorian to the Julian calendar in Britain (and to January 1 being the start of the year, instead of March 25), required the skipping of 11 days that September, so people went to bed on September 2nd, and woke up on September 14th. So Isaac Newton’s birthday slid into January, and from 1642 to 1643. (Washington’s birthday also got moved, from Feb 11, 1731, O.S., to Feb 22, 1732, N.S.)

These kinds of accounting adjustments in the world around us make history slippery; what was real then, is not now. Isaac Newton, father of modern physics, famed victim of rogue fallen apple, lived in a world of unreality, too. He believed in alchemy, and magic—as did many of his time. Witchfinders stalked the land, with political power behind superstition.

But he changed our understanding of the real. In between his work as a scholar, he was appointed to be Warden of the Royal Mint, and there took on a major role—stabilizing the currency. In the Spring of 1696 he joined the Mint—in what had been to that point a medieval patronage gig. Little was expected in such a role. No Warden had previously taken much of an interest in the activities of the Mint’s clerks, who were tasked with tracking counterfeiters.

Newton, however, took it seriously.

England’s currency at the time was based on a silver standard. Coins were made of silver and weighed fixed amounts, dictating their value. This was a challenge when the value of silver, relative to other goods, fluctuated. England was in debt thanks to ongoing wars; its coins were often worth more (as bullion) than their face value in pounds. Silver coin was taken from the country to be sold in markets abroad.

A popular currency crime was “coin clipping” (cutting or shaving a small amount of silver from the edge of coins, and filing the coin down or even melting and recasting with a lower percentage of silver). Counterfeiting and clipping were capital crimes, but apparently widespread. Newton started cracking down.

He interviewed alleged coin clippers and counterfeiters, traced criminals to their homes, and visited the prisons to find accomplices. He helped draft the Coin Act of 1796, which penalized coin manufacture of any kind. But he went bigger: launching the Great Recoinage.

Coins in circulation were collected by the Mint, melted down, and reminted at fixed weights. This involved a production line of 500 men, and branch mints at different cities around the country. It took four years to smelt most of England’s money supply.

In 1699, Newton was promoted to Master of the Mint, a role he held until his death in 1727. He applied scientific precision to creating regular coins, and hired an engraver to create more beautiful designs.

Later he would play a role in fixing the value of the gold guinea at 21s, inadvertently helping to move England from the silver to the gold standard.

His own fascination with metallurgy and magic made him a focused administrator. It didn’t make him much of an investor—he lost a fortune in the South Sea Bubble, reportedly saying, “I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of men.”

But his steady hand helped England’s currency stay strong, through a turbulent period. He knew that people had to trust the system for the system to work. He was knighted by Queen Anne in 1705.

After his death, Newton would appear on coins himself—the first time though not on official currency. Newton was used on unofficial halfpenny “tokens” issued by private businesses in the 1790s, to deal with the fact that there were not enough coins in circulation in the growing economy.

Perhaps as a nod to his work as a scientist, a Caduceus is on the other side.

But he would be featured on British currency, including the £1 banknote issued in 1978.

His impact on the economy would last, along with his impact on the world of science, even as he downplayed his own genius: “If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.”

The post Anniversary of Isaac Newton’s Birth was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.