The Return of Quantitative Easing

December 2025 marks the official end of the largest cycle of quantitative tightening the Federal Reserve has ever undertaken.

From a peak of $8.93 trillion in June 2022, the Fed has allowed $2.4 trillion in maturing assets to roll off its balance sheet. But Chair Powell announced on December 10 that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has decided it must begin expanding its balance sheet again to maintain “ample reserves”—code for maximizing policy discretion and insulating itself from market forces.

Before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the Fed conducted monetary policy primarily through open market operations. Raising its target interest rate—the rate in the overnight interbank lending market—required the Fed to sell bonds from its balance sheet until the supply of reserves contracted enough to push up the federal funds rate (FFR). Conversely, lowering the target rate required purchasing bonds until reserves expanded sufficiently to pull the FFR down.

Another feature of this approach was that the Fed also “defended” its target against changes in market conditions. If demand for reserves (liquidity) increased in private markets, the Fed would respond by increasing the supply of reserves through additional bond purchases. In this framework, the Fed both engaged with and responded to private markets.

That changed after the GFC, when the Fed dramatically expanded its balance sheet, lowered its target rate to near zero, and began paying interest directly to banks on reserves held at the Fed. After 2008, interest rate targeting became largely a matter of adjusting the rates the Fed paid to banks and other counterparties, rather than buying or selling bonds in the open market.

This shift allowed the Fed to purchase bonds with relative impunity, since the interest rate it targeted was no longer directly constrained by reserve supply. The result was a series of bond-buying programs known as quantitative easing (QE). Several rounds of QE under former chair Ben Bernanke added trillions of dollars to the Fed’s balance sheet. By December 2019, the balance sheet stood at roughly $4.1 trillion, up from less than $1 trillion a decade earlier.

Under Chair Powell, however, the Fed added nearly $5 trillion more during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The most recent round of belt-tightening was sorely needed, particularly given elevated inflation over the past four years. Even so, the current balance sheet—$6.539 trillion—is still $2.44 trillion larger (nearly 60 percent) than it was in December 2019. That amounts to an 8 percent annualized growth rate in the Fed’s balance sheet, compared with roughly 4 percent annualized inflation over the same period.

So $6.54 trillion is inadequate for “ample reserves”? Color me skeptical.

Yet the problems associated with monetary expansion remain. Prices are still rising at a 3 percent annual rate, well above the Fed’s stated 2 percent target. Other dynamics may therefore be influencing the Fed’s decision to restart QE while simultaneously lowering its target overnight rate.

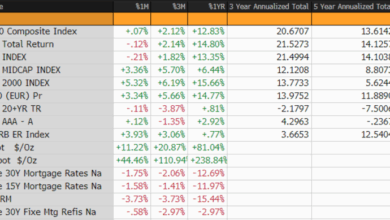

The proposed $40 billion purchase in December will undo the last several months of tightening. Here is the pace at which the Fed’s quantitative tightening unfolded:

| Quarter End Date | Total Assets (in Trillions of USD) | Quarterly Reduction (Approx.) |

| Q2 2022 (June 29) | $8.932 Trillion | −$28 Billion |

| Q3 2022 (Sep 28) | $8.847 Trillion | −$85 Billion |

| Q4 2022 (Dec 28) | $8.641 Trillion | −$206 Billion |

| Q1 2023 (Mar 29) | $8.740 Trillion | +$99 Billion (Increase) |

| Q2 2023 (June 28) | $8.347 Trillion | −$393 Billion |

| Q3 2023 (Sep 27) | $7.986 Trillion | −$361 Billion |

| Q4 2023 (Dec 27) | $7.737 Trillion | −$249 Billion |

| Q1 2024 (Mar 27) | $7.531 Trillion | −$206 Billion |

| Q2 2024 (June 26) | $7.340 Trillion | −$191 Billion |

| Q3 2024 (Sep 25) | $7.152 Trillion | −$188 Billion |

| Q4 2024 (Dec 25) | $7.013 Trillion | −$139 Billion |

| Q1 2025 (Mar 26) | $6.740 Trillion | −$273 Billion |

| Q2 2025 (June 25) | $6.673 Trillion | −$67 Billion |

| Q3 2025 (Sep 24) | $6.608 Trillion | −$65 Billion |

| Q4 2025 (Dec 10) | $6.539 Trillion | −$69 Billion (to date) |

Still, there must be some explanation for the change in course. Perhaps, given the fracturing within the FOMC, we are witnessing a bit of old-fashioned horse trading.

President Trump has applied significant pressure on Powell and the FOMC to lower rates quickly. Powell and his colleagues have responded by reviving a form of monetary easing that does not require cutting the target federal funds rate. Reigniting QE appears to serve that purpose, allowing the Fed to ease policy while preserving at least a modicum of institutional self-respect rather than resorting to outright capitulation.

Powell also faces defections from both sides of the committee. Board member Stephen Miran favored a half-point cut, while Austan Goolsbee and Jeff Schmid voted to maintain the current target. (Somewhat ironically, three dissents played out in an almost identical fashion in September 2019, when James Bullard pushed for a half-point cut while Esther George and Eric Rosengren voted to hold the target rate steady.)

Given that the Fed pays banks and other counterparties the lower end of its target interest rate range, lowering the FFR reduces their interest bill. During the recent cycle of tightening and rate increases from 0.25 to 0.5 percent to over 5 percent, that interest bill ran into the hundreds of billions of dollars. Though the Fed can create all the dollars it needs to make payments, from an accounting standpoint, it garnered huge operating losses and even larger balance sheet losses during the recent cycle.

Restarting quantitative easing (the purchase of short-term Treasury debt) will ease the federal government’s borrowing costs. As interest rates on newly issued short-term Treasurys decline, the alarming rise in federal interest payments—now over a trillion dollars a year—may begin to level off.

The government’s insatiable appetite for borrowing may also bolster the FOMC’s claim that its balance sheet, though far larger than in 2019, remains less than “ample.” The Fed’s floor system—setting target interest rates independently of bond purchases—rests on the existence of a massive supply of reserves. That supply keeps the effective market rate for borrowing reserves below the “floor” rate the Fed pays on reserves. After all, why would a bank lend reserves to another bank at 2 percent when the Fed will pay 3.5 percent?

But rapid growth in the demand for reserves—effectively, demand for borrowing—driven by persistent federal deficits will exert upward pressure on interest rates, potentially pushing them above the Fed’s target.

I am not sure that would be so bad, just as I am not sure inflation modestly below the Fed’s 2 percent target would be so bad either. Yet with a voracious Treasury needing to borrow trillions more each year, the FOMC appears to believe it is time to expand the balance sheet through QE once again. Chair Powell may hope to thread the needle among competing views within the committee, but the Fed’s current course looks uncomfortably close to capitulation to political pressure. If inflation remains at or above 3 percent over the next year, we will have our answer.

The post The Return of Quantitative Easing was first published by the American Institute for Economic Research (AIER), and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.