Madeira: Europe’s Forgotten Miracle

In 1978, a tiny, dirt-poor Atlantic island of 250,000 souls decided to do the one thing Brussels now treats as heresy…

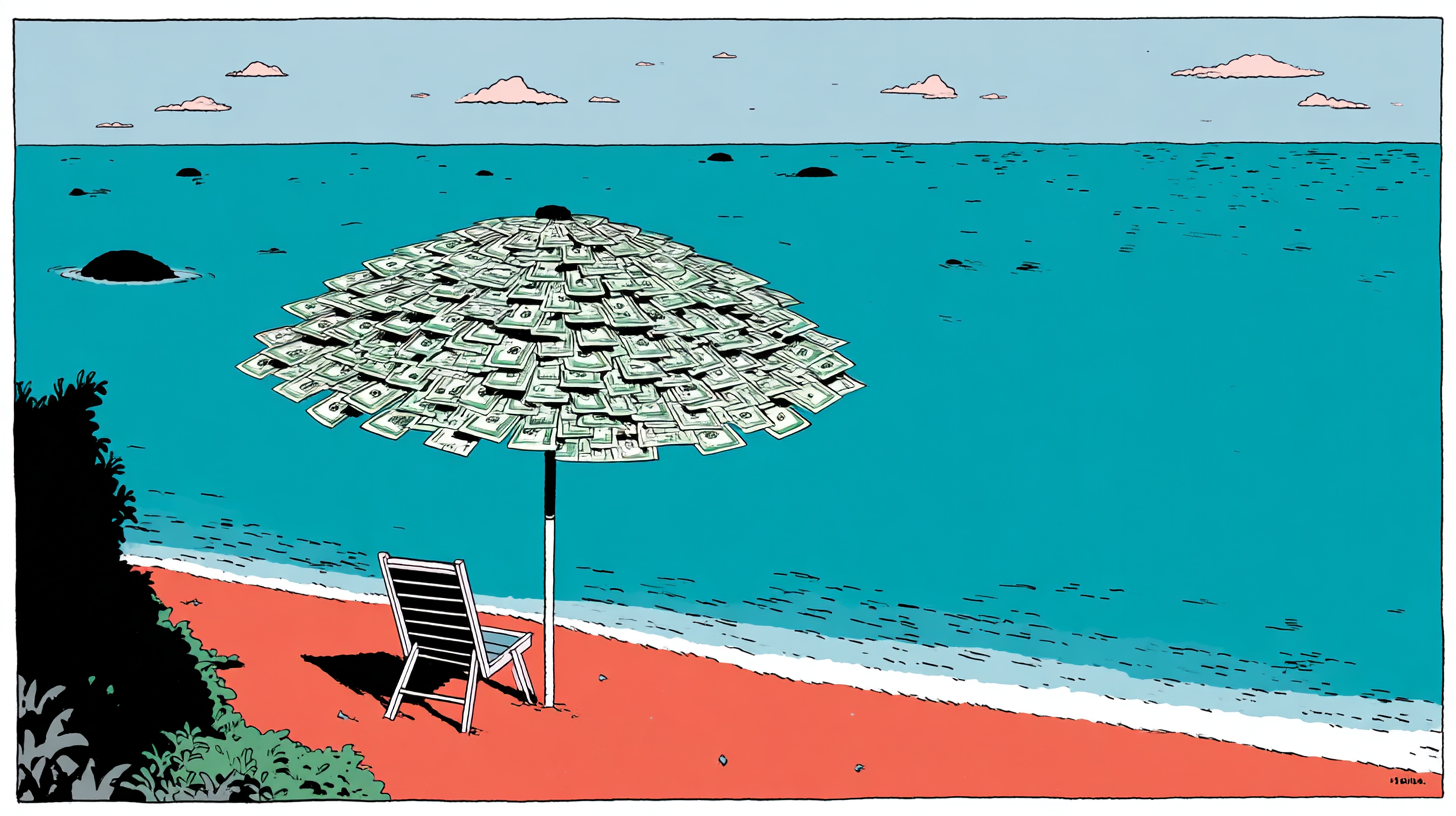

It cut its corporate tax rate to the bone and built Europe’s last genuine special economic zone.

And now, 47 years and countless European Union investigations later, that same island shows the opposite of decline: its GDP has quadrupled since 1995; it has narrowed the gap with the European average by more than 20 percentage points; unemployment in recent years has fallen below mainland levels; and its 5% corporate tax regime has been legally renewed until 2033.

No oil. No tech miracle. No massive subsidies. Just lower taxes and the freedom to keep the money you earn. This is the story Europe’s central planners don’t want you to hear.

Half a century ago, the Portuguese island of Madeira was one of the poorest places in Europe: double-digit unemployment, mass emigration, suitcases made of cardboard, and an economy that barely went beyond bananas, Madeira wine, and handicrafts. Insularity was not a postcard feature, but a structural obstacle to any serious development.

Then came regional autonomy in 1976. Shortly after, in 1978, the newly elected regional president, the larger-than-life Alberto João Jardim, put forward a simple and, at the time, radical idea: “We cannot change geography, so let’s change the tax code.” Jardim would go on to govern the island for the next 37 years.

Lisbon said yes. The Portuguese government knew that sporadic subsidies and public works projects would never solve a deep structural problem. Moreover, given that Portugal was preparing to join the European Economic Community, it needed a credible development plan for its poorest regions. The EEC of the late 1970s and early 1980s, far more liberal than today’s European Union, not only validated the project but explicitly classified it as a legitimate instrument of territorial cohesion.

And so the Madeira International Business Centre (commonly known as the Madeira Free Zone) was born: sharply reduced corporate income tax, exemptions in the industrial free-trade area of Caniçal, and a competitive regime for international services. All of this capped off with the strategic masterpiece, the International Ship Registry of Madeira (MAR) with low fees, flexible legislation, and unquestionable EU flag credibility. Add lightning-fast administrative procedures, one-stop licensing, and full freedom to repatriate capital and profits. Madeira stopped competing on location and started competing on tax intelligence.

The economic impact was nothing short of profound. Within a few years, the island ceased to depend almost exclusively on agriculture and tourism. It became a respected European hub for international business services and maritime activities.

Management consultancies, holding companies, logistics operators, yacht-management firms, and tech companies moved in. The MAR registry attracted shipowners from Greece, Germany, Scandinavia, and the world’s largest cruise and cargo operators, turning Madeira into one of the largest and most respected open registries in Europe.

Unemployment fell steadily to levels consistently lower than on the Portuguese mainland. Tax revenue soared, not because rates were high, but because the tax base exploded with new investment, new companies, and genuine economic activity. Between 1995 and 2022, Madeira’s GDP grew at an average annual rate of 5.2%,comfortably beating mainland Portugal’s 3.9% (both nominal; DREM/INE long series, 2024).

To understand just how dramatic the turnaround was, consider that in the late 1970s, Madeira’s GDP per capita was barely 40% of the European average. By 2023 it had soared to roughly 75% of the EU average, a near-doubling in relative terms while receiving far less in EU structural and cohesion funds per capita than almost any other ultra-peripheral region.

The International Ship Registry alone is now the third-largest in Europe and the flagship of choice for several of the world’s top twenty cruise companies. More than 1,000 vessels fly the Madeira flag, generating hundreds of millions of euros annually in registration fees, legal services, classification societies, and maritime insurance, almost all of it new money that did not exist on the island before 1987.

Meanwhile, the broader International Business Centre hosts over 2,500 licensed companies, many of them subsidiaries of Fortune 500 groups that use Madeira as their European holding or treasury platform. These firms directly employ several thousand highly skilled Madeirans (with an average salary well above the Portuguese mainland) and sustain an ecosystem of law firms, auditors, trust companies, and IT providers that would have been unimaginable 50 years ago.

Perhaps the most telling statistic: in 1970, roughly one in four working-age Madeirans lived abroad. Today, the diaspora still exists, but net migration is positive, and the island regularly appears in the top three Portuguese regions for new business creation per capita.

That success made Brussels deeply uncomfortable. Starting in the 1990s, the European Commission launched repeated investigations for “excessive state aid.” Caps were imposed, reports were commissioned, local job-creation quotas were demanded. Nothing managed to kill the regime. In 2015, the Commission tried again, this time requiring “economic substance”: real offices, real employees, real activity physically located on the island. The irony is delicious: the rule designed to weaken the zone ended up strengthening it. Companies opened proper offices, hired Madeirans, and rooted themselves in the local economy.

To abolish the regime outright, Brussels would have to renegotiate and rewrite the EU treaties themselves, a political mountain no one in the Commission has ever been willing to climb.

Today, in a Europe that has spent the last 15 years systematically crushing every remaining pocket of tax competition and that proudly led the charge for the OECD’s global 15% minimum corporate tax, Portugal has just renewed Madeira’s 5% rate until 2033. The island remains the only territory in the entire EU with a fully fledged, fully legal special economic zone, that has been repeatedly attacked, yet repeatedly renewed, for the simple reason that it works.

This should not be treated as an exotic exception. It should be the rule.

More than a stunning tourist destination or the birthplace of Cristiano Ronaldo, Madeira is living proof that competitive tax policy can transform a remote, peripheral, resource-poor region into an economic success story. Brussels fears the precedent precisely because it dismantles the central dogma of tax harmonization: tax competition does not destroy states.

It builds them.

The post Madeira: Europe’s Forgotten Miracle was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.