Denying the Affordability Crisis Won’t Change the Data

A new wave of public polling and media coverage suggests that the Trump administration’s claim that “there is no affordability crisis” is increasingly being rejected by American households.

Recent reporting shows rising public skepticism toward assertions that prices are stabilizing or falling. Donald Trump has repeatedly dismissed cost-of-living concerns as a “Democrat hoax” or a “con job,” yet consumer frustration over housing, energy, food, health care, and insurance remains widespread. Even as the administration insists that purchasing power has improved, most voters report that everyday necessities remain far more expensive than just a few years ago, undercutting the official narrative and widening the credibility gap between political messaging and lived reality. Prices have risen, broadly, since the 2024 election.

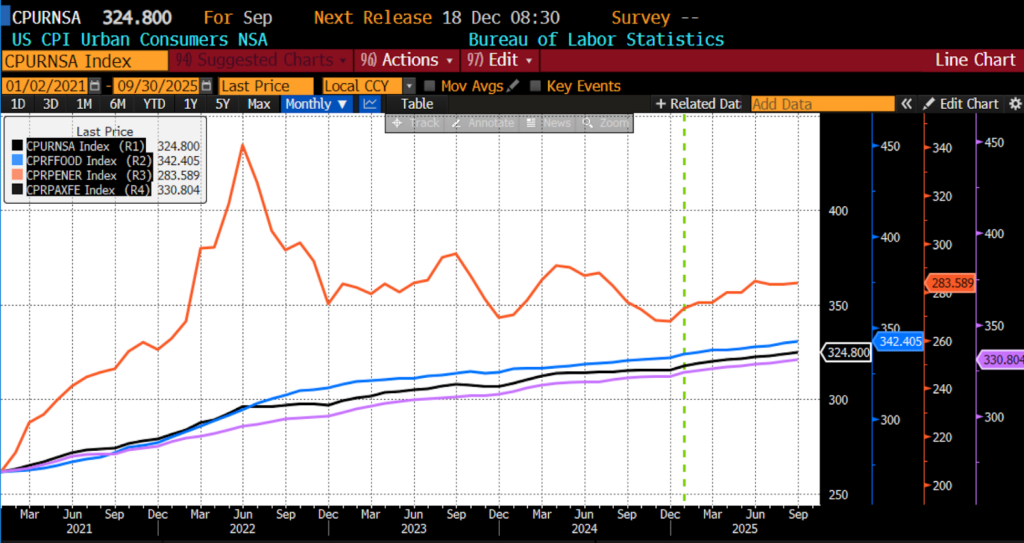

CPI Food, Energy, Core, and Electricity, November 2024 – September 2025

Prices are of course much higher than they were prior to the pandemic, and although the annual rate of inflation may have slowed, cumulative price levels are dramatically above pre-2020 norms. Housing, insurance, utilities, groceries, and many categories of durable goods remain far out of line with historical purchasing-power trends. The relevant measure for households is not the year-over-year inflation rate, but whether wages have kept pace with total price increases. Real affordability depends on the relationship between prices and incomes, not simply the direction of inflation. Even official wage and income measures continue to lag cumulative inflation since early 2021, which means that the broad affordability problem has not meaningfully eased.

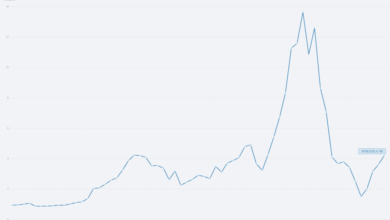

Economic lags matter — a core principle of sound economics, and especially the free market tradition. Policy interventions, whether fiscal or monetary, operate with considerable delays. The enormous fiscal expansion of 2020 to 2021, combined with extraordinary Federal Reserve accommodation and unprecedented money supply growth, produced predictable consequences with the customary lag. Prices have been rising for years, and the cumulative effect is still visible today. Supply shocks, monetary excess, and regulatory distortions do not disappear overnight.

Indeed, the Federal Reserve’s tightening campaign has so far merely slowed additional damage; it has not undone the prior shocks. Historically, disinflation produces a difficult adjustment process: credit tightens, asset prices reprice, real household incomes lag, and consumption patterns shift. This stage is inherently unpopular, but unavoidable. Instead of acknowledging that households are in this difficult transition, the administration has attempted to leap over the adjustment period with rhetoric, insisting that prices are already headed down and affordability restored. Yet Americans still confront elevated grocery prices, historically high mortgage rates, persistent insurance premium increases, and costly medical bills. When government asserts improvement while households experience strain, voters believe their wallets rather than the White House.

In recent months, Trump has repeatedly asserted that inflation has already been brought under control since he returned to office. In October 2025 he said that the Federal Reserve had cut rates and declared that “inflation has been defeated.” In a November 10 White House statement titled “NEW DATA: Lower Prices, Bigger Paychecks,” the administration claimed that Trump’s economic agenda was “delivering real results,” including tamed inflation, falling everyday prices, and rising wages. In an interview aired on November 11, Trump said that “costs are way down across the board,” emphasizing lower gasoline and interest rates, and at a McDonald’s–themed public appearance he again claimed that gas prices were “way down” and that prices generally were “coming down” under his administration. More broadly, recent White House messaging and Trump’s campaign-style remarks have described his first year back in office as producing “lower prices” and improved affordability for American families.

Yet the underlying data tell a very different story — one that American consumers immediately recognize. Prices continue to rise across most major categories and remain substantially above the Federal Reserve’s inflation target. Wages have increased more slowly than prices over the past several years, meaning real purchasing power remains depressed relative to pre-pandemic conditions. A few categories — notably gasoline in 2025 — have indeed declined. But most have not. The pattern bears a striking resemblance to Joe Biden’s widely discredited claim that inflation was “over nine percent” when he took office: a political narrative at odds with statistical reality.

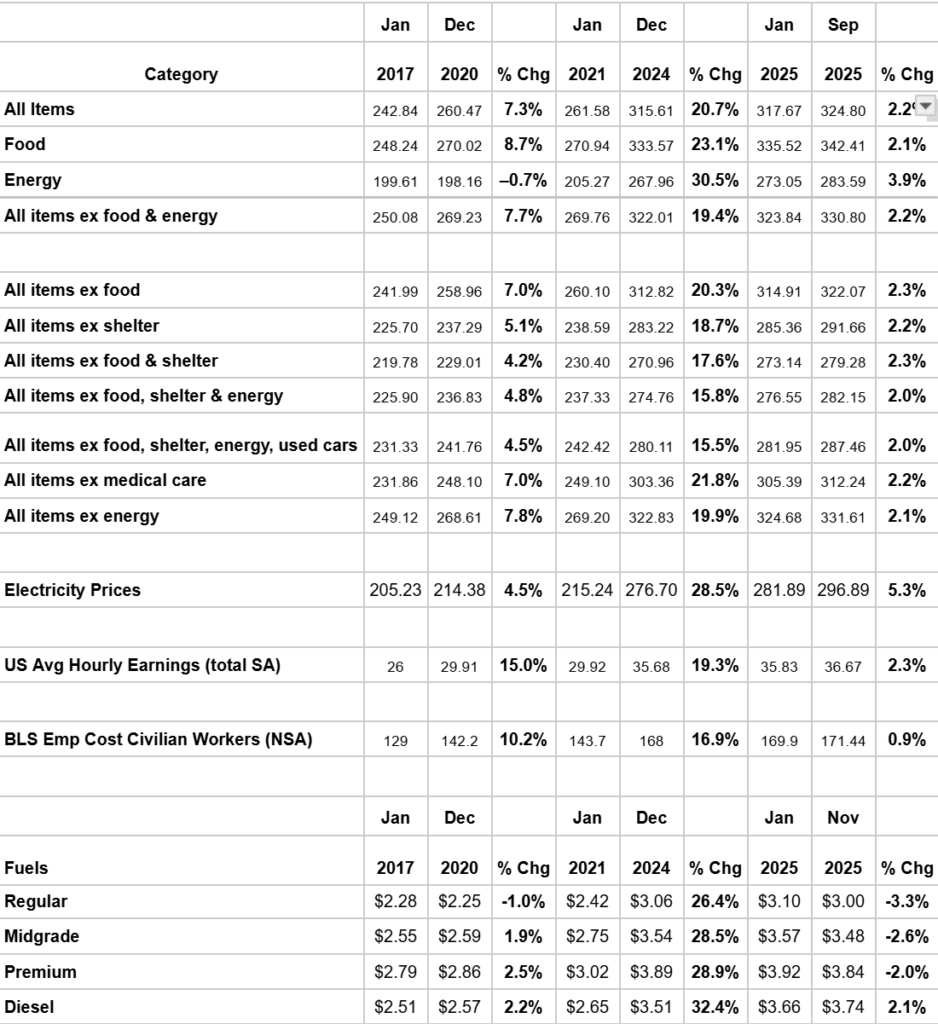

Between January 2017 and December 2020, the CPI-U rose about 7.3 percent, food about 8.7 percent, and the All Items Less Food and Energy index about 7.7 percent. Energy was essentially flat. Wages rose at roughly similar rates. Affordability pressures were building, but the alignment of wages and prices meant that a sustained affordability crisis had not yet emerged.

The picture changes dramatically starting in early 2021. From January 2021 through December 2024, the CPI-U rose nearly 21 percent, the Food index climbed more than 23 percent, and the All Items Less Food and Energy index gained roughly 19 percent. Energy prices rose more than 30 percent. Meanwhile, wage growth was substantially weaker; generally in the mid- to high-teens over the period. Depending on the specific wage measure, incomes were flat or negative to price increases through most of 2021 to 2023 and only slightly positive in late 2024. The divergence marks the beginning of the affordability crisis: prices outran wages, and they have continued doing so.

Early 2025 data confirm a continuing affordability squeeze. From January to September 2025, the All Items CPI rose about 2.2 percent, food about 2.1 percent, energy nearly 4 percent, and core indices about 2.2 percent. Nominal wages rose only modestly, and real gains were minimal. The affordability problem did not end with the turn of the calendar or the election; it persists as long as cumulative price increases outstrip wage gains. Moderating inflation only slows the rate at which affordability erodes; it does not undo the erosion already suffered.

CPI All Items, Food, Energy, and Core, 2021 – present

Electricity costs have risen relentlessly, climbing from an index level of about 215 in early 2021 to roughly 277 by the end of 2024, and advancing further into the mid-290s in 2025 — an almost uninterrupted increase that underscores how even essential utilities remain substantially more expensive than before the affordability crisis began.

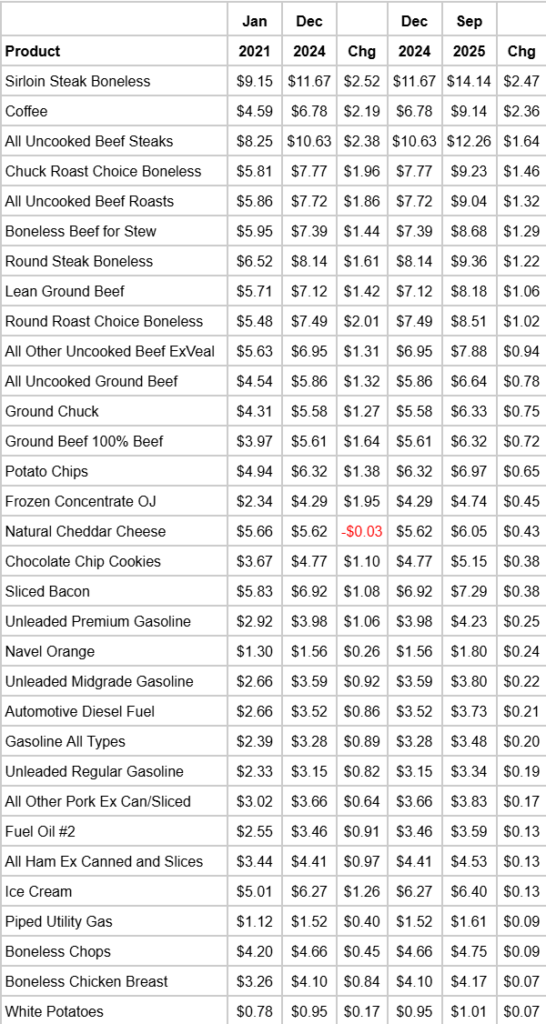

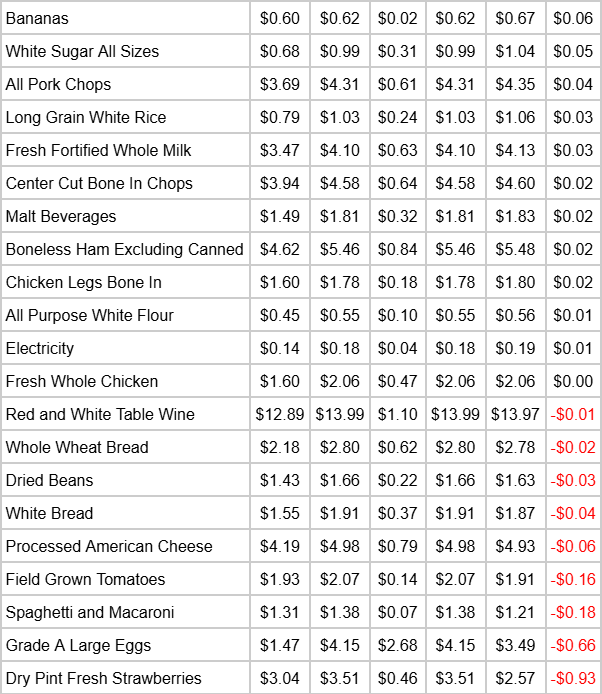

The same pattern holds in individual food categories. Sirloin steak, coffee, beef cuts, and many packaged goods are all measurably higher now than in January 2025. A few categories have fallen from recent peaks, but not enough to reverse the cumulative increases since 2021. In fact, several items rose more in the first nine months of 2025 than during the entire 2021 to 2024 period. This suggests not only that elevated prices remain embedded in household budgets, but that some categories continue to accelerate even after “high inflation” has supposedly ended. Put plainly, the affordability crisis that began in 2021 has not faded; it has evolved into a stubborn, category-specific price pressure affecting everyday goods.

Tariffs are a component of the affordability problem: rather than removing the cost-raising policies of prior years, the administration has expanded them, even though tariffs are taxes that raise input prices, distort supply chains, and weaken competitive discipline — all of which generate costs ultimately borne by producers and consumers alike.

Insisting there is no affordability crisis while simultaneously increasing import costs is analytically incoherent, especially when many of the underlying pressures — monetary excesses, pandemic distortions, and longstanding regulatory barriers — predate Trump’s return to office. Instead of denying these strains, the administration could acknowledge them and credibly explain their origins while advancing market-oriented solutions: expanding competition, removing regulatory bottlenecks, and eliminating tariffs, which would quickly relieve price pressures and reduce costs economy-wide.

The irony is that the administration could, but for inexplicable intransigence, actually win this issue. By recognizing the affordability crisis and offering market-oriented remedies, it could restore credibility and articulate a coherent economic vision. Instead, by taking the precise tacticthat its predecessor didand attempting to evadeand mislead citizens, it forfeits the strongest argument available: yes, there is an ongoing affordability crisis; it did not start under the current administration, but it continues; it partially owes to policy lags, and partially to interference with trade (as the administration has already conceded); and truly free-market reforms are the only lasting way out. By denying what Americans plainly experience, the administration turns a solvable economic challenge into a major political liability while leaving households to absorb costs that sound policy could meaningfully reduce.

The post Denying the Affordability Crisis Won’t Change the Data was first published by the American Institute for Economic Research (AIER), and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.