Money Makes the World Go ’Round

“Imagine money falling from the sky. Would you slip a tenner into your pocket before you told anyone? Chances are, most of us would trouser a few notes rather than inform the authorities.” This is the opening of economist and banker David McWilliams’s rollicking history of money, and his description of Operation Bernhard, the Nazi campaign to destabilize Britain by flooding the country with counterfeit cash.

Lenin tried a similar ploy in Russia. Despite having different political beliefs, they “both understood the phenomenal power of money: undermine money and you undermine the fabric of society.”

That right there is McWilliams’s underlying theme: money is the fabric of society. He wants people to understand how cash shapes our world. As he puts it: “Despite being a fully paid-up member of the economist tribe for many years, I’ve concluded that most economists do not really understand money.”

His description of the earliest markets, and how coinage in the ancient world allowed the development of long-distance trade, is clear and evocative. For the Sumerians, money was linked to agriculture. A shekel represented the value of a bushel of grain:

The granary, one of the most important institutions in any ancient city, regulated the supply of grain and thereby the supply of money, much like a modern-day central bank. The more grain, the better the harvest, the more money in circulation.

Pretty soon after the arrival of money, we discovered the value of lending it. That gave money itself a price: the rate of interest. In his words: “[I]nterest isn’t merely a price; it is also a code, a mini-encyclopedia of information about the person we are lending to, the chances of success, the risk in the region, the competition in the market, the technological infrastructure, and a whole host of other variables.”

Lenders in Ancient Greece were figuring out the concept of the FICO score, in a very basic way—it was borrowing that enabled growth. A farmer could borrow against next year’s harvest, in order to buy tools today, while the lender made a bet that the farmer would pay him back. All with money that they were both trusting would retain its value.

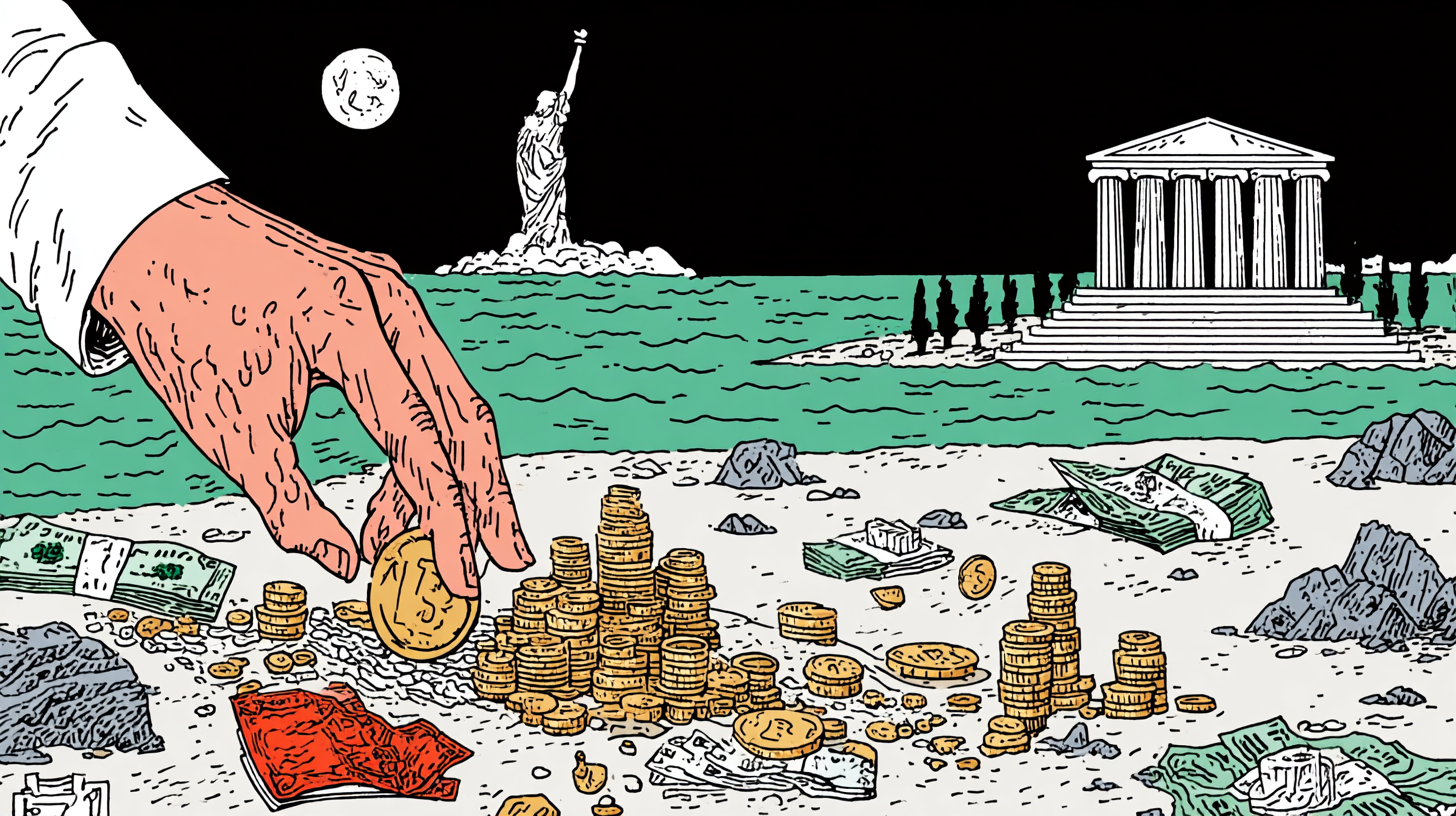

That trust is essential to the system is a key point for McWilliams. Today, if you hand me $10, I’m trusting many things at once: first, that this piece of printed paper has a meaning, a meaning that will be understood by a shopkeeper when I try to exchange it later that day for a coffee; second, that the government which issued this bill will back it; third, that you are not a forger, and the bill you give me is genuine. Our entire relationship with money is based on trust.

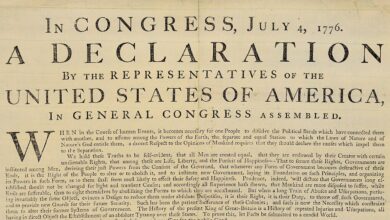

Racing through millennia, McWilliams swings us from the kingdom of Lydia to the influential printing press of Johannes Gutenberg. For the history of money, Gutenberg’s press was significant in two ways: enabling the printing of cash, obviously; but also helping to push forward the Reformation, which was a cash grab in its own way:

A major attraction of this new religion was that a converting monarch could steal the assets of the old religion. England’s Henry VIII, known also as the Great Debaser, a very poor money manager, found the idea of confiscating Church lands extremely tempting. Kings and princelings all over Germany followed Henry’s example, expropriating Church property.

It really wasn’t long, in human history, between the arrival of money and the understanding that it was always better to have more of it.

In a clear and engaging style, McWilliams laces together the importance of Hindu-Arabic numerals (especially the concept of zero) for the development of money, and the effect of panics and fads, like Dutch tulipomania, a commodity bubble that seems amusing in retrospect but was devastating at the time.

The creation of money enabled investment, and speculation, and eventually the joint-stock company. The trade networks of the Dutch East India Company made the Netherlands wealthy, despite being a tiny nation with few natural resources, particularly the historic stores of wealth and power for nations: territory and manpower. Having spent hundreds of years being smacked around in various European conflicts, the Dutch had little of either.

But what they did have was a willingness to trade—and for the government to sponsor companies in which the public could invest:

By effectively tying the fortunes of the company to the state, the government encouraged shareholding, coaxing in people who would otherwise never have owned shares. They were creating an investment opportunity out of a speculative venture, and that investment would generate a stream of income for a broad section of the population, embedding financial capitalism deep in the Dutch psyche. Holland was on its way to becoming a shareholding culture mediated by money.

In the 20th century, the nature of money shifted again. No longer backed by the value of gold or silver, fiat currencies are backed only by our belief in the stability of the country that issues them. “The stronger and more robust the state and its organs, the stronger and more credible the currency.”

Yet despite his focus on trust and credibility, McWilliams is not going long on cryptocurrency or alternative forms of exchange. Surely, the market will decide if individuals trust any particular coin?

As he writes: “The economy we experience every day and live in is not a model; it is an adapting complex system that is spontaneous and unpredictable.” Just as abandoning the gold standard once seemed unimaginable, people shifting to different forms of money may come to seem more plausible as time goes by.

If you want to understand just how cash operates, how banks create it, and how we all play our part in defining its value, this book is an engaging introduction.

The post Money Makes the World Go ’Round was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.