Spain’s Persistent Poverty Problem

Spain’s Socialist-led government claims to have reduced socioeconomic inequality to “historic lows.” In some respects, this seems to be true. Spain currently scores 31.2 on the Gini income inequality index, down from 31.5 in 2023 and 33 in 2021. Earlier this year, adult unemployment—always problematically high—dropped to 10.29%, the lowest rate since 2008. The Spanish economy is outperforming those of all other EU nations, and was named the best in the world by The Economist in 2024. Prosperity and opportunity all ’round, it might seem.

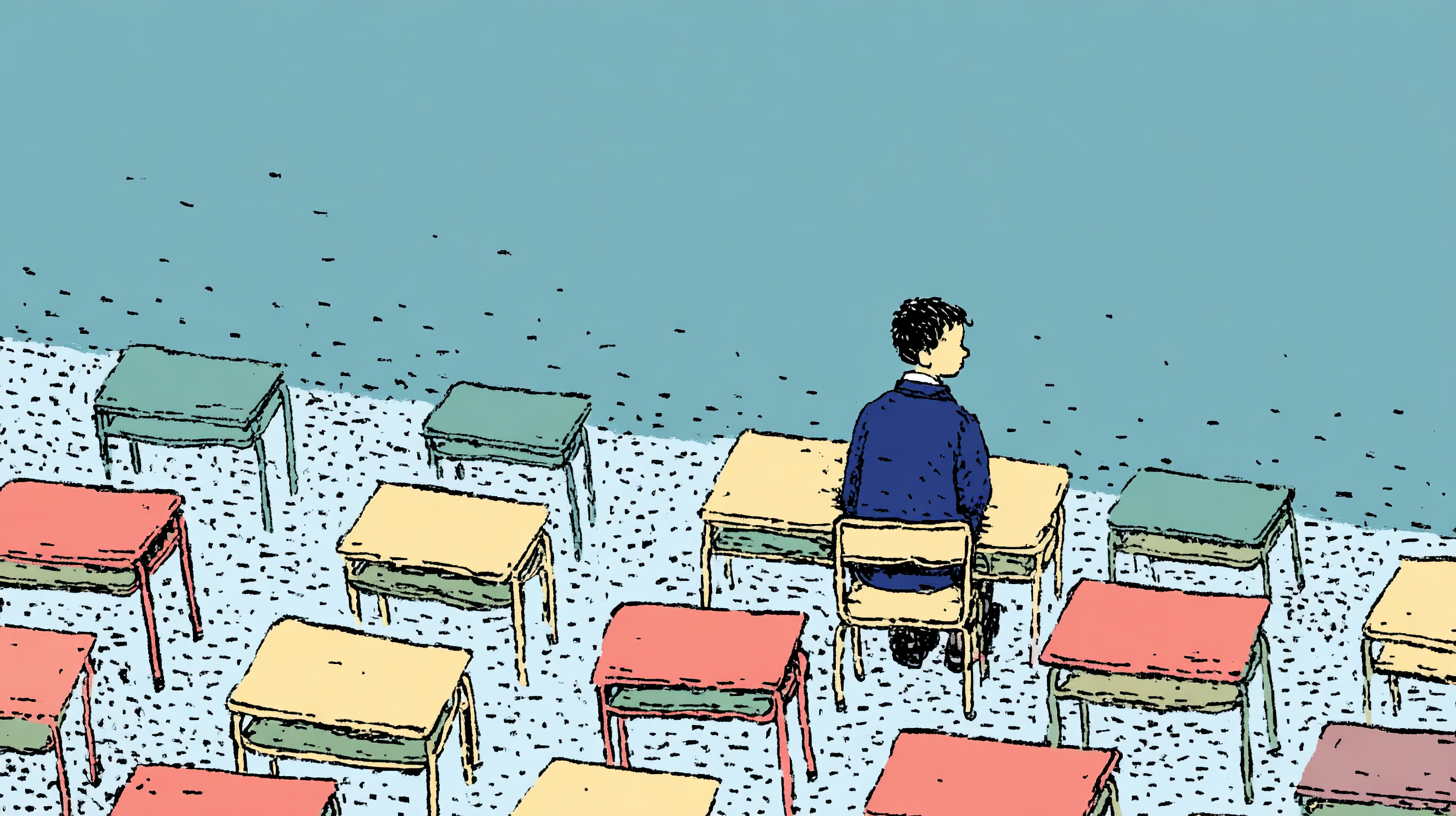

Not quite. Lurking behind the positive statistics are some uncomfortable truths about Spain. Its adult jobless rate remains the highest in the EU, and is several percentage points above the bloc’s average of 6.2%; Youth unemployment is the second-highest in Europe (after Estonia) at 26.6%; and the same percentage of the population—around 12.7 million people—live at risk of poverty or social exclusion. The persistence of these problems suggests that they are deeply rooted in Spanish society, recurring in self-perpetuating cycles. One of the root causes rarely makes headlines: child poverty.

According to recent data, about 1 in 3 children in Spain, or around 34%, live at risk of poverty or social exclusion. In late 2023, a UNICEF report named it the worst in the EU for child poverty, ranking it 36th out of 39 EU and OECD countries. The report found that more than 1 in 4 children live in poverty in Bulgaria, Colombia, Italy, Mexico, Romania, Spain, Turkey, and the US, and that “national wealth does not guarantee that a country will prioritize the fight against child poverty.” Save the Children has published similar findings—for example, that 1 in 3 Spanish children live in homes that cannot afford a summer holiday. Ironically, almost half of them live in the Canary Islands, one of Europe’s major tourist destinations.

It is no coincidence that Spain is one of the EU’s most unequal countries and also has the bloc’s worst child poverty rate. In a report published by the OECD in September, which analyzed inequality amongst people aged 25 to 59 in 32 countries, Spain ranked 8th with a score of 37% (the US placed second with 42%, suggesting that the American dream is somewhat more achievable if your parents live in Scarsdale or Los Altos). The report also found that 35% of income inequality in Spain is owed to factors beyond the individual’s control, such as place of birth, gender, and parents’ socioeconomic background.

The vicious cyclical relationship between child poverty, youth and adult unemployment, and inequality has been corroborated by the European Anti-Poverty Network (EAPN). In a study released last year, the EAPN found that 1 in 4 people who grew up in poor households in Spain was living in poverty in 2023, “representing a higher poverty rate than the general population (25% compared to the overall rate of 20.2%).”

In other words, children who grow up in deprived circumstances, and with limited access to education, struggle to find jobs as young people, and many of them become parents to children who are in turn raised in poverty. Spanish children from single-parent families, the majority of which are headed by women, are especially vulnerable. According to the EAPN, the poverty rate for children raised by single parents is 21.6%, compared to 17.5% for those brought up by two parents.

Historically, the structure of Spain’s labor market has exacerbated its poverty and inequality levels. Red tape and tax still discourage employers from hiring, and make things difficult for entrepreneurs. The Spanish tourism industry accounts for almost 14% of the country’s total jobs, but most of these are low-paying temporary contracts, some for just a few days or weeks. Temporary contracts have long been the scourge of Spain’s labor market, and previously represented almost 30% of all employment agreements. But due to labor reforms introduced by Pedro Sánchez’s government in 2021, that figure has now been reduced to about 13%.

Sánchez has also tried to tackle child poverty directly. After taking power in 2018, he created the position of High Commissioner for the Fight Against Child Poverty, currently occupied by Ernesto Gasco—although it’s not obvious what exactly Gasco has been doing for the last seven years. Sánchez has also stressed the role played by his flagship welfare policy, the Minimum Basic Income scheme (IMV, in its Spanish acronym), introduced to help struggling households during the pandemic, and the Child Support Supplement, the combined funds for which he says amount to €3 billion. “Never before has such an investment been dedicated to the fight against child poverty,” claims Sánchez.

The problem with throwing money at impoverished households is that children are not the guaranteed beneficiaries. So far, the government claims that the IMV has reached over 2 million people living in 674,000 households, 67% of which contain children. It therefore calculates that the scheme is “protecting” 816,000 children—but to make that claim, it would have to know how exactly the money is being spent. Spain’s persistently high child poverty rates indicate that it’s not all going to textbooks, extra-curricular activities, and nutritious meals. A more fundamental criticism of the IMV is that it is not helping to break the cycle of child poverty, adult unemployment, and inequality. By disincentivizing work, by reducing the need to strive, it keeps poor households at roughly the same level, albeit technically lifting them out of poverty.

Bureaucracy is also reducing the societal impact of Sánchez’s anti-poverty spending. The EAPN report cited above contains a damning summary of people’s experiences of the social protection system in Spain. “Often,” it noted, “those receiving benefits feel that the system is designed to discourage rather than assist, putting up bureaucratic barriers that turn the process of obtaining aid into an exhausting and frustrating experience.”

Though it sounds paradoxical, the Spanish government’s anti-poverty measures, especially the IMV, might be failing precisely because they’re too focused on poverty. Of the 60,000 people interviewed by the authors of a 2009 book called Moving out of Poverty, fewer than 1% said that their lives had been materially improved by anti-poverty programs. On this view, governments should concentrate more on creating prosperity than combating poverty. “Creating prosperity,” of course, is a vague phrase—but it does hint at why increased welfare spending is never enough to break the generational transfer of poverty. If Sánchez hopes that the IMV scheme will solve Spain’s deepest societal problems, he’s asking too much of it.

The post Spain’s Persistent Poverty Problem was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.