IMF’s Outlook: Not Great

The IMF’s October 2025 update to its World Economic Outlook delivers a modest upward revision, but lurking behind this seemingly optimistic shift are deeper currents shifting global growth and capital flows.

The Fund, originally forecasting in July that global growth would sit at 3% in 2025, now projects 3.2% for 2025, and 3.1% in 2026. A small upgrade on the face of it, yet it is worth remembering that the global economy exceeds $100 trillion, meaning even a fraction of a percent represents significant value.

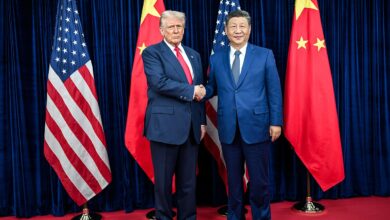

More importantly, the slight upgrade in percentage reflects two contrasting forces: the flip side of higher trade tensions under President Trump’s tariff policy, and a (perhaps temporary) surge in private-sector investment around artificial intelligence.

The US tariff escalation, promised by Donald Trump in the 2024 election campaign and delivered since, has been more muted than many feared. The IMF notes that stronger-than-expected supply-chain resilience, rerouted trade flows, and the absence of widespread retaliation have cushioned the blow. Though adjustments to global trade flows have been blunted by the tariffs, in many ways this has left the United States playing catch-up rather than leading global economic changes.

In particular, the Fund emphasizes that resisting retaliatory tariffs provided an upside of roughly 0.3 to 0.4 percentage points to global output compared with earlier forecasts. Meanwhile, AI-related investment is acting as a near-term growth driver—especially in the US—though the Fund warns this may be a speculative boom more than a long-term productivity surge. As FEE has pointed out elsewhere, the resource-intensive AI industry ballooning now might burst before it achieves maturity.

Yet, even with the improved forecast, the IMF stresses that the world economy remains on a lower-growth path than in prior decades. The muted impact of tariffs so far carries two lessons: businesses are adapting more swiftly by front-loading imports and shifting sourcing; and the costs of protectionism may arrive with a lag.

The IMF cautions that the full effect “has yet to materialise.” Inflation pressures remain uneven. It also warns of “rising odds of disorderly correction” in financial markets, given stretched valuations, elevated debt, and the links between regulated and non-bank financial institutions.

Beyond these cyclical risks, the deeper story is geographical. As North American and European growth stagnates, emerging economies (particularly across Southeast Asia) are becoming increasingly attractive to investors seeking higher returns and lower tariff exposure. The fact that $100 billion has been invested in the region is testament to this. India, for example, is projected to expand by 6.6% in 2025, making it one of the few major economies with consistent momentum despite global headwinds.

The current IMF scenario reinforces that trend. With tariffs proving less disruptive than anticipated, companies and investors are accelerating their pivot from the old Western axis toward the new Asian one.

Multinationals are shifting procurement and manufacturing hubs toward ASEAN economies such as Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia, where supply-chain risk and tariff exposure are relatively lower. Investors, meanwhile, are seeking equity and infrastructure opportunities that capture regional growth and demographic advantages. As growth expectations cool in the US and Europe, Asia’s relative resilience stands out.

The AI investment boom, too, is increasingly transnational. South-East Asian economies are positioning themselves as regional nodes within the AI ecosystem, offering a combination of talent, low-cost infrastructure, and pro-innovation policy.

This means that as Europe and North America grapple with tariffs, inflation, and slower expansion, Asia absorbs a growing share of the upside. The result is not simply cyclical strength but a gradual structural shift in the geography of growth—one that recasts Southeast Asia from peripheral to pivotal in global capital markets.

The IMF’s numbers hardly suggest a world economy in full recovery. Yet the very fact that forecasts have been revised up, rather than down, reveals a more adaptive global system. Trade is diversifying, technology is investing in itself, and capital is finding new routes around old bottlenecks. As the IMF’s managing director Kristalina Georgieva remarked, the world has “shown more resilience than expected.” The center of gravity is shifting, and Southeast Asia continues to emerge as the clearest beneficiary of that global rebalancing.

The post IMF’s Outlook: Not Great was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.