Playing Chicken with the Federal Budget: The Rational Stupidity of Shutdowns

“Chicken” is a game where two people, or two groups, want different things, in a context where “I win/you lose.” That is, there are no gains from exchange or compromise, and the loser is not only worse off, but embarrassed.

Government shutdowns are chicken games. Knowing that gives us a way to understand what is happening.

When I teach “chicken” I tell students to imagine you and James Dean, both in souped up 1967 Mustangs, are facing each other on a narrow road, about 1 mile apart. The game begins, and you both accelerate hard, to show you mean business.

If you both go straight (the road is too narrow to pass each other), there is a huge explosion and everyone dies. If you go straight and James swerves, you win and James is humiliated. And vice versa.

If you both swerve, then you both regret having passed up an opportunity to win. And your partisans, standing by the road and cheering, are embarrassed at your cowardice.

Who will win? Whoever cares more about winning, or cares less about dying. Of course, both of you tell everyone “I’m not afraid to die!”, but those are just words. Each player wants to win, but is in fact afraid to die. So, “I swerve, [you swerve or don’t swerve]” is better than “straight, straight.” I know that, you know I know that, I know you know, and so on.

As you get closer, you can see your opponent’s face, set in grim determination. Suddenly, James Dean does something amazing: he throws his steering wheel out the window! He can’t swerve. My only choice now is to go straight also (he dies, but so do I) or swerve (embarrassing, but I avoid dying). By throwing his steering wheel out the window, James commits to going straight, which means he wins.

Of course, I have played chicken before, so I know what to do. I immediately throw my steering wheel out the window.

(Record scratch…) What? I want to die?

Wait for it. James throws out another steering wheel, and so do I. We are both throwing steering wheels out the window like crazy. Because each has a stack of them, on the front seat beside us.

Shutdown Background

Government shutdowns are not exactly a fiery crash, but they seem irrational. If you understand chicken, though, it makes more sense.

If a government in a parliamentary system fails to pass its budget, that is likely to collapse the government and trigger a new election. But that’s not true in Washington. In the US, the House and Senate have to agree, and the President has to sign the resulting bill. Partisan control can be divided (as it has been for nearly 90 of the years since 1800), or the minority party in the Senate can filibuster, or the President can veto.

It wasn’t always a chicken game. The famous 1879 rider fights between (Republican) President Hayes and a Democratic Congress were contentious, but there was no shutdown. The dispute involved election-related riders on Army and marshals funding, which the Democrats were using to try to end Reconstruction. The conflict dragged on for months, but partial appropriations were passed and only limited sums were actually withheld. The nonsense was kept in DC, where it belongs.

But the system showed signs of strain in the 1970s: there were six substantial gaps in budget coverage between 1977 and 1980. But agencies continued operation, even if funding expired, because it was assumed that funding would be restored.

That changed in 1980–81, when Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti issued opinions interpreting the Antideficiency Act (enacted in 1884, amended in 1950 and 1982) to require agencies to cease operations, except for narrow “essential” activities. Those opinions — grounded also in the Constitution’s Appropriations Clause — created the modern “shutdown,” now codified in the Office of Management and Budget Circular A-11.

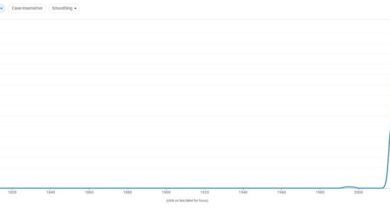

Since the rules changed in 1981, there have been a number of actual shutdowns, where government workers were sent home, without pay (though at least until now the pay has always been restored retroactively). Counting only funding gaps in which shutdown procedures were followed (i.e., agencies closed and employees were furloughed), the episodes are:

· Nov 20–23, 1981 — 2 days

· Sep 30–Oct 2, 1982 — 1 day

· Oct 3–5, 1984 — 1 day

· Oct 16–18, 1986 — 1 day

· Oct 5–9, 1990 — 3 days

· Nov 13–19, 1995 — 5 days

· Dec 15, 1995–Jan 6, 1996 — 21 days

· Sep 30–Oct 17, 2013 — 16 days

· Jan 19–22, 2018 — 2 days

· Dec 21, 2018–Jan 25, 2019 — 34 days (or 35, depending on how you count)

The Logic of Chicken

The shutdown seems pointless, from an outside perspective. Everyone would be better off if we simply implement the deal that will be agreed on later, and skip the intervening inconveniences. And, make no mistake, there will be inconveniences: tens of thousands of applications, cases, tax returns, licenses, refunds, and other mandatory paperwork will be delayed for no reason.

Many of the 2.25 million federal employees will work, but there will be no savings because they will still be paid, and rent on all those empty federal offices will still be due. It seems possible that the Trump administration will use the shutdown as a chance to push through permanent reductions in force, but even if that happens, the cost savings will be negligible.

To understand why all this is happening, despite the costs, and in spite of the fact that there will be a deal, one must think in terms of the payoffs to this peculiar version of “chicken.”

First, the usual payoffs are reversed, in the sense that many — perhaps most — members of Congress prefer “straight, straight” to “swerve, swerve.” Sure, the fiery crash is expensive for the country, but it benefits political leaders and the rank-and-file to appear to stand firm against the enemy. Of course, each side prefers that the other would give in, but there are few costs to being stubborn.

Second, the “steering wheels” are different: you aren’t trying to scare your opponent. The reason to make statements of obdurate resolve is to appeal to “your base.” Instead of being costly, boasting about your toughness is a benefit.

Further, in a federal system the temporary shutdown of the central government is nearly unnoticeable for most people, for several days and perhaps for some weeks. Even if there is a fiery crash, it’s far away for most of us and doesn’t affect our lives much.

What all this means is that government budget shutdowns are rational, the predictable consequence of the strategic setting. The drivers of each party can blame the refusal of the other side to cooperate, and they actually get credit for the shutdown. This could change if voters stopped rewarding politicians for these craven, empty demolition derby shows. But voters actually seem to be interested, and so the parties obligingly get back out on the road to give us the show we say we don’t want, but certainly deserve.

The post Playing Chicken with the Federal Budget: The Rational Stupidity of Shutdowns was first published by the American Institute for Economic Research (AIER), and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.