A New Pacific Trade Highway

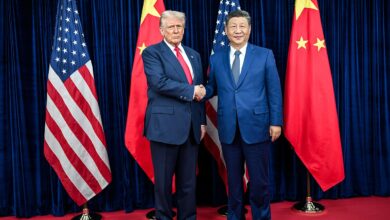

When President Trump announced a new 100% tariff on Chinese imports, in retaliation for Beijing’s latest export controls on rare earth elements, markets saw only the headline risk. But the real story lies beyond the ticker: a structural reordering of global trade. The world’s supply chains, long anchored to the Chinese mainland, are splintering.

Capital is scattering across Asia’s periphery, and shipping routes that once followed predictable trans-Pacific lines are being redrawn into a new web of uncertainty and opportunity. Alongside an eastward turn worth $100 billion in investment, the trends of the last 30 years of global financial flows are being upended.

The tariffs, nominally intended to protect American industry, have become a catalyst rather than a disruption. China’s tightening of export rules on rare earths, a sector that underpins global technology and defense manufacturing, has already caused shipments to fall sharply this autumn. That decline is deliberate: Beijing is weaponizing its market dominance to exert pressure on Washington and signal that supply chains remain a form of leverage. The Trump administration’s countermeasures (broad tariffs and new fees on Chinese-built ships docking in American ports, extensively disrupting the transshipment trend of recent years) seek to contain that leverage, yet they also deepen the fragmentation of global commerce.

Rather than simply pushing prices up, these measures are accelerating a diversification that had already begun. Companies that once treated China as the irreplaceable factory of the world are now spreading their risks across what trade analysts call a “China+1” or even “China+N” model.

Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and India are attracting new investment in electronics, textiles, and automotive components as manufacturers seek to route goods through lower-tariff jurisdictions. The result is not a clean decoupling but a messy rewiring. Supply chains have become a geopolitical map of caution: firms are trading efficiency for resilience, scale for redundancy.

The shift is visible not only in production patterns but in capital flows. As direct investment into China cools, regional neighbors are absorbing the spillover. Vietnam’s industrial parks are oversubscribed. India, once considered too bureaucratic to rival China, has become a preferred hedge for multinational manufacturers. Even Indonesia and the Philippines are attracting capital to their nascent semiconductor and battery sectors. Japan, South Korea, and Australia, meanwhile, are benefiting from intra-Asian trade and renewed logistics investment.

The diversification of supply has brought with it a diversification of shipping. The old trans-Pacific artery—container ships running directly from Shanghai or Shenzhen to Los Angeles—has been replaced by a tangle of feeder routes linking smaller ports.

Vietnam to California, India to Seattle, Malaysia to Texas: new pathways are forming, each less efficient but more politically secure. As cargo is redistributed, congestion is rising at smaller Southeast Asian ports ill-equipped for the surge. Where once were economies of scale are now a jigsaws of capacity constraints and freight premiums. The UNDP recently warned that the region is entering a period of “disruption, diversification, and divergence,” where the old efficiencies of globalization give way to a new hierarchy of regionalization.

Rare earths illustrate the logic of this new order. Despite a truce in this key market that indicated potential collaboration, Beijing’s controls have added more elements to its restricted list, while export licenses are now required even for goods containing trace amounts of Chinese material. Western buyers are scrambling to rebuild stockpiles or fund alternative mining projects in Australia, the US, and Africa.

Yet even as these efforts multiply, China retains the advantage in refining and magnet manufacturing, where most of the value—and vulnerability—resides. The commodity is no longer just a raw material but a political instrument, and its trade routes have become strategically sensitive corridors across the Pacific.

Markets will not be grateful for the ongoing politicization of trade commodities, materials, or even corridors in this new multipolar world, and may seek more stable regions instead.

Other sectors are already following suit. Refined metals, semiconductor wafers, and advanced ceramics are all acquiring what analysts now call a “geopolitical freight premium.” The price of shipping is no longer determined solely by weight or distance but by risk: sanctions exposure, transit chokepoints, and the prospect of retaliatory tariffs.

The Strait of Malacca, a thin strip of sea between Malaysia and Indonesia connecting the Pacific and Indian Oceans through which much of East Asia’s energy imports flow, has become emblematic of this anxiety. China’s so-called “Malacca Dilemma” (a narrow maritime bottleneck) has only intensified as supply lines diversify. New routes through India and Australia’s northern ports aim to dilute that vulnerability, but at the cost of longer, less efficient journeys.

For investors, the geography of opportunity is shifting. The old paradigm of massive centralized production in China feeding global demand is dissolving. In its place is a mosaic of mid-sized markets, each demanding infrastructure, ports, and localized industry. Those who adapt to this multipolar economy will profit not from scale but from foresight: anticipating friction rather than chasing volume. The Pacific is no longer a single oceanic highway connecting two superpowers; it is a network of competing corridors, each with its own risks and rewards.

Tariffs protect domestic industries; or so claim their proponents. In practice, they have exposed how interdependent the global economy has become.

As Washington and Beijing exchange economic fire, it is the periphery—Southeast Asia, India, Australasia—that absorbs the blast and finds new room to grow. The new trade map of the 2020s is not drawn along ideological lines but logistical ones. Where goods can flow freely, capital follows. Where they cannot, prices rise and markets realign. In that sense, Trump’s tariffs may yet achieve something their authors never intended, and their opponents never foresaw: the birth of a genuinely diversified trade system connecting Pacific nations, bound less by politics and more by necessity.

The post A New Pacific Trade Highway was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.