The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics honors three economists whose work embodies an idea first coined by Joseph Schumpeter: creative destruction. Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt have each advanced our understanding of how technological progress drives human prosperity. As Schumpeter described, every technological advance has two faces. It destroys by rendering old methods obsolete, yet it creates by flooding the market with new goods and more efficient ways of meeting human needs.

The Nobel Committee’s focus on creative destruction feels particularly relevant today, in an era dominated by fears over artificial intelligence. Public debate often centers on the destructive side of AI: the jobs it may displace or the industries it could transform beyond recognition. Far less attention is paid to its creative side: the new goods and services that will emerge, the efficiencies that will make certain tasks economically viable for the first time, and the opportunities that arise when resources are freed from older, less productive uses.

Among this year’s laureates, economic historian Joel Mokyr stands out. A professor at Northwestern University, his work shares affinities with that of Deirdre McCloskey. While McCloskey emphasizes the importance of bourgeois dignity—the revaluation of entrepreneurship—as a central factor in the Industrial Revolution, Mokyr has highlighted the power of ideas. As he writes in The Enlightened Economy, “Economic change depends, more than most economists think, on what people believe.” Beliefs and discourse, together with material change, form the missing pieces of the modern growth puzzle.

For Mokyr, the innovator is a kind of rebel: someone unwilling to accept the world as it is, determined instead to reshape it. Prosperous economies rely on innovation as their fuel, yet innovation itself depends on an institutional environment that welcomes this creative rebellion. Without openness to experimentation and dissent, even the most talented minds will lack the space to turn new ideas into progress.

Aghion and Howitt, meanwhile, pioneered what macroeconomists call endogenous growth theory. Philippe Aghion, affiliated at the time of the award with the Collège de France (INSEAD) and the London School of Economics, and Peter Howitt, of Brown University, joined forces to challenge earlier growth models. Unlike earlier models that treated growth as driven by forces outside the economy—such as mere capital accumulation or random technological shocks—Aghion and Howitt examined how innovation arises within the system itself. For them, technological possibilities are nested within the institutional framework of each society, much like a chick developing inside an egg. Economies advance or stagnate depending on how well they encourage or suppress creative destruction.

Sustained growth, in the view of this year’s laureates, is not simply a matter of investment or research spending. It requires openness to technological change and the willingness to accept the turbulence it brings. Governments must resist the temptation to indulge their inner Luddites. Overregulation and protectionist policies can stifle entrepreneurial experimentation, halt investment, and ultimately suffocate creativity. Limiting the influence of interest groups that seek to shield themselves from competition is just as crucial. When established firms dictate the political agenda, they often do so at the expense of the innovators who might one day replace them.

Friedrich Hayek once warned that the Nobel Prize in Economics—formally the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel—could be dangerous, granting its recipients an aura of authority that no social scientist should possess. He feared that laureates might be treated as oracles, asked to pronounce on matters far beyond their expertise, and that the public might mistake their opinions for revealed truth. Hayek’s caution was well-founded: economics, properly understood, should cultivate humility rather than hubris.

Yet even a broken clock is right twice a day. While many economists whose contributions deserve recognition—names such as Armen Alchian, Harold Demsetz, Arnold Harberger, or Israel Kirzner—have never received the honor, this year’s prize strikes a rare and worthy chord. By celebrating those who have deepened our understanding of innovation, institutions, and the dynamics of creative destruction, the committee has reminded the world that economic progress depends not on avoiding change but on harnessing it.

Additional Reading

For readers eager to explore the work of the 2025 laureates:

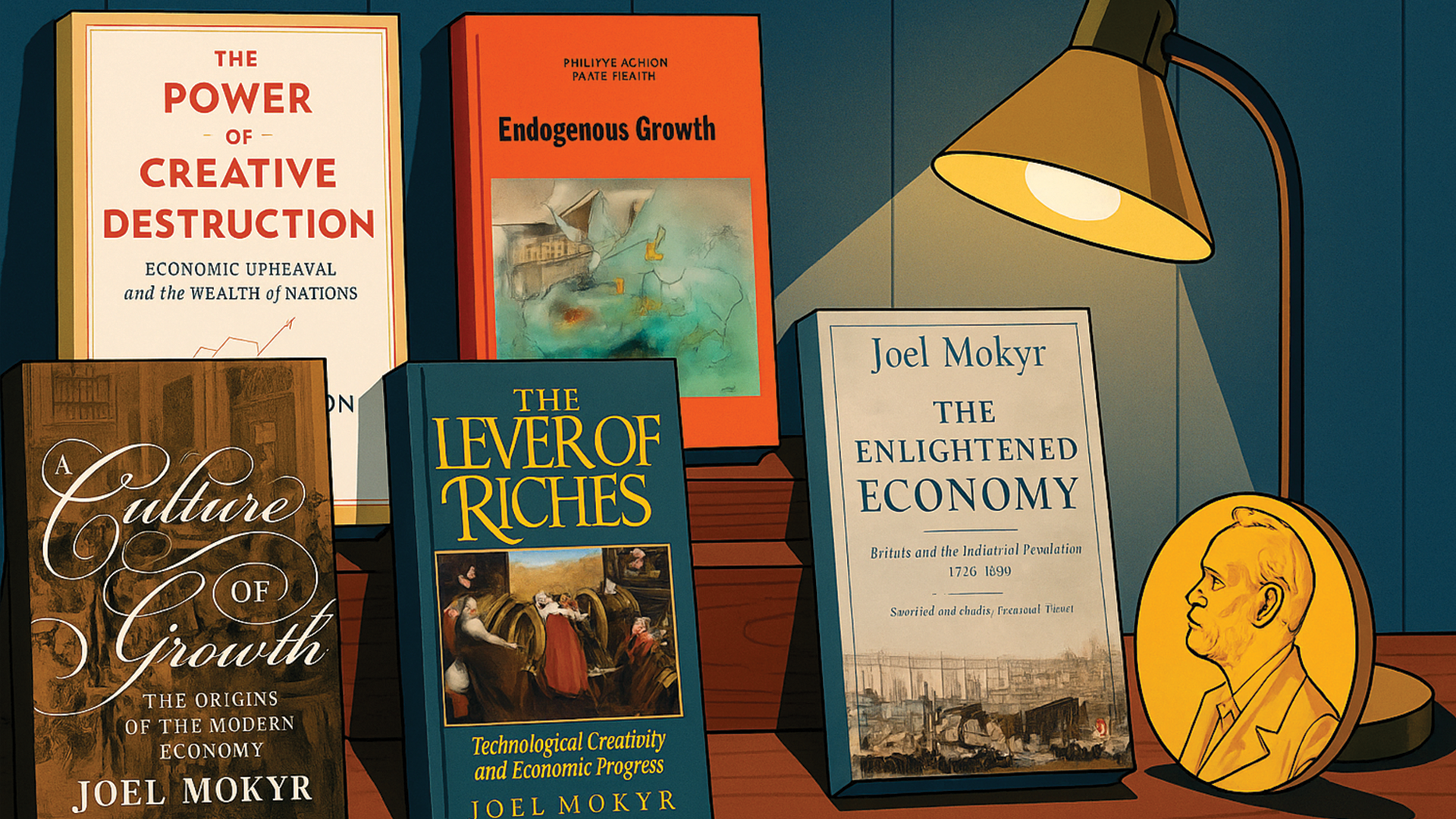

By Joel Mokyr:

The Lever of Riches — An account of technological change and the historical conditions that nurtured it.

The Enlightened Economy — A study of how ideas and discourse shaped the Industrial Revolution in Britain.

A Culture of Growth — A continuation of his earlier work, showing how networks like the Republic of Letters helped spread science and technology.

By Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt:

Endogenous Growth Theory — The foundational text modeling the process of creative destruction within modern growth theory.

By Philippe Aghion (with Céline Antonin and Simon Bunel):

The Power of Creative Destruction — A lucid exploration of how today’s living standards are the product of the innovations enabled by free-market capitalism.

The post The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.