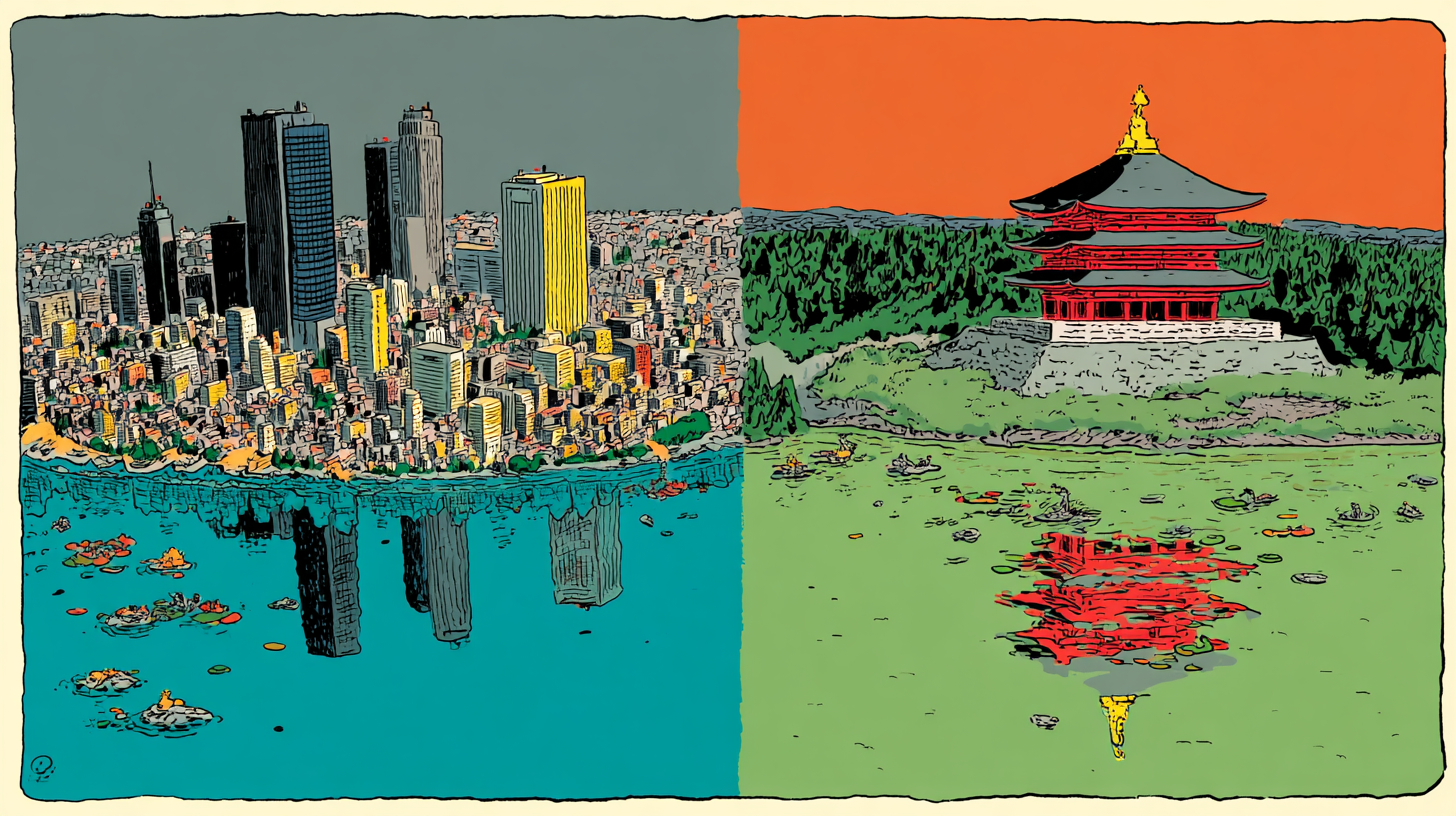

Looking East

Global investors are turning their interest toward Asia, amid a wider realignment of foreign direct investment (FDI), trade flows, and investor confidence.

A quiet but profound reorientation of global capital is underway, as Goldman Sachs’s global wealth division estimates investors have poured more than $100 billion into Asian assets this year. The region’s markets are attracting inflows once dominated by the United States and Europe. This is not the cyclical rush of hot money that typically follows rising yields or a commodity boom; it reflects a strategic diversification away from Western concentration and the recognition that Asia’s capital markets—especially in Japan, India, and Southeast Asia—are becoming the structural center of gravity for global investment.

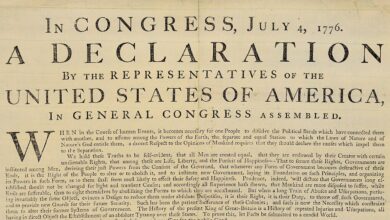

The timing is not accidental. The post-pandemic decade has left investors uneasy about the durability of US growth and the political uncertainty surrounding fiscal management and trade. As Goldman’s Asia wealth head remarked, “The era of the all-US portfolio is over.”

A decade of extraordinary dollar strength has also created an underappreciated asymmetry: global portfolios became overweight in US equities, but underexposed to the world’s most dynamic consumer bases. As the Federal Reserve signals a long plateau for interest rates, asset managers are looking east for yield, growth, and political hedging.

Nowhere is this more evident than Japan, where investors have rediscovered a market once written off as perennially stagnant; there is a stronger stock market, and a Prime Minister economically inspired by Britain’s own Margaret Thatcher has been elected. Private credit and corporate reform are driving a quiet renaissance: KKR’s expansion of its Tokyo operations and its prediction of a “private credit boom” underscores how local companies are tapping global capital in ways unthinkable a decade ago. Japan’s stock market, meanwhile, has enjoyed record inflows thanks to renewed shareholder activism and the yen’s weakness, which enhances export competitiveness. For global wealth managers, Japan is a convenient compromise: developed-market governance with emerging-market pricing.

Singapore and Hong Kong have also re-emerged as financial magnets. Singapore’s political stability and its reputation for legal predictability make it an obvious beneficiary of China’s capital retraction. HSBC data show that global high-net-worth clients are increasingly relocating wealth to Singapore, the UK, and Switzerland as China’s domestic markets stagnate. Yet Hong Kong’s story is more complex. The Financial Times recently reported record inflows from mainland investors seeking exposure to offshore listings despite ongoing political friction. Paradoxically, what was once considered a liability (its hybrid identity between China and the West) has become its greatest advantage.

Beyond the financial hubs, the Indian market continues to attract both passive and active capital. The Economic Times highlighted how India has become a natural recipient of diversification away from the US, aided by steady GDP growth and deepening domestic consumption. Global asset managers increasingly treat India as a standalone allocation, not merely a component of “emerging markets.” This is a subtle but profound shift: it elevates India from a satellite to a system-defining economy, with its own corporate giants and a growing role in supply-chain diversification away from China.

The restructuring of global supply chains since the pandemic has accelerated this realignment. COVID-19 exposed how dangerously centralized production networks had become; especially those dependent on China’s manufacturing base. In the years that followed, firms embraced near-shoring and friend-shoring, relocating manufacturing to politically aligned or geographically closer economies.

Southeast Asia, India, and Mexico have each benefited as Western manufacturers diversified inputs and logistics routes to reduce exposure to geopolitical risk. According to the Financial Times, the breakdown in transshipment routes has effectively ended the practice of re-exporting through China, creating new hubs in Vietnam and Indonesia. This reconfiguration of trade has not only redrawn the map of production but reshaped global capital flows, toward the very regions now absorbing investment on a scale unseen in decades.

Institutional research backs up the anecdotal evidence. BNP Paribas Asset Management and AXA Investment Managers both note that “divergence calls for diversification,” as regional growth differentials and currency cycles encourage investors to rebalance across continents. The logic is straightforward: when the world’s largest economy also carries the world’s largest fiscal deficit, over-concentration becomes a liability. The IMF’s latest data show that Asia now accounts for more than half of global growth, and for investors weary of volatility in Western politics, this is no longer a speculative bet but a structural realignment.

Modern Diplomacy’s analysis of the same trend observes that the $100 billion inflow marks a “psychological turning point” for fund managers, many of whom had previously viewed Asia as riskier than its reward justified. But the data now contradict that assumption: the MSCI Asia ex-Japan index has outperformed the S&P 500 on a total-return basis for the first time in over a decade, while regional bond markets offer both higher real yields and lower correlation with Western inflation shocks.

It would be mistaken, however, to assume that Asia is insulated from risk. China’s property crisis continues to weigh on regional sentiment, and the divergence between democratic and authoritarian regimes introduces political uncertainty of its own. Yet for many institutional allocators, the calculus has changed: rather than avoiding risk, they are seeking to diversify it.

Just as the 1980s saw Western capital flow into Latin America and Eastern Europe in search of frontier returns, the 2020s are witnessing a rotation toward the Indo–Pacific, a region defined not just by low costs but by demographic and technological ascendancy.

The deeper implication is philosophical. For much of the post-Cold War era, global investment strategies were premised on the assumption that the United States would remain the undisputed anchor of economic stability. That assumption no longer holds. The rise of Asia as a capital destination does not mean a rejection of the West, but rather suggests the maturation of a genuinely multipolar financial order. Investors, weary of political volatility in Washington and diminishing returns in Europe, are rediscovering what diversification was always meant to be: not chasing the next hot market, but building resilience through plurality.

In that sense, the $100 billion turning east is not a story about yield curves or carry trades; it is a signal that the geography of confidence has changed. The capital that once circled Wall Street now orbits a wider constellation, from Tokyo to Mumbai to Singapore, and with it the balance of financial power begins quietly, but decisively, to tilt.

The post Looking East was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.