Wealth Is Green

The environmental debate is often hijacked by discourses that view the market and capitalism as irreconcilable enemies of nature. However, recent history shows just the opposite: economic development, combined with innovation, has provided the most effective solutions to major ecological challenges.

An emblematic example is the ozone layer. In the 1980s and 1990s, scientists discovered that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), found in refrigerators and aerosols, were eroding this natural atmospheric barrier essential to life on Earth. The news generated enormous apprehension: many predicted imminent catastrophe, even the collapse of civilization. The topic gained ground in popular culture, with films like The Sky’s on Fire, which depicted burning skies and humanity threatened by ozone depletion.

However, reality took a different path. Within a few years, the market reinvented itself. Production chains were reorganized, new technologies developed, and safe alternatives to CFCs created. This process also relied on rare international cooperation, consolidated by the Montreal Protocol, which established clear targets for the replacement of these harmful substances. The effort was successful. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the production and consumption of CFCs were gradually phased out. By 2009, approximately 98% of the substances controlled by the treaty had been eliminated from the global market.

Today, the ozone hole still forms annually over Antarctica during the spring, but tends to close in the summer when stratospheric air currents from lower latitudes mix. This cycle repeats itself, but with clear signs of recovery. Scientific assessments indicate that the ozone layer is being restored as expected and should return to pre-1980 levels in the coming decades. The threat once considered irreversible is on its way to being overcome, thanks to the market’s adaptability and international cooperation.

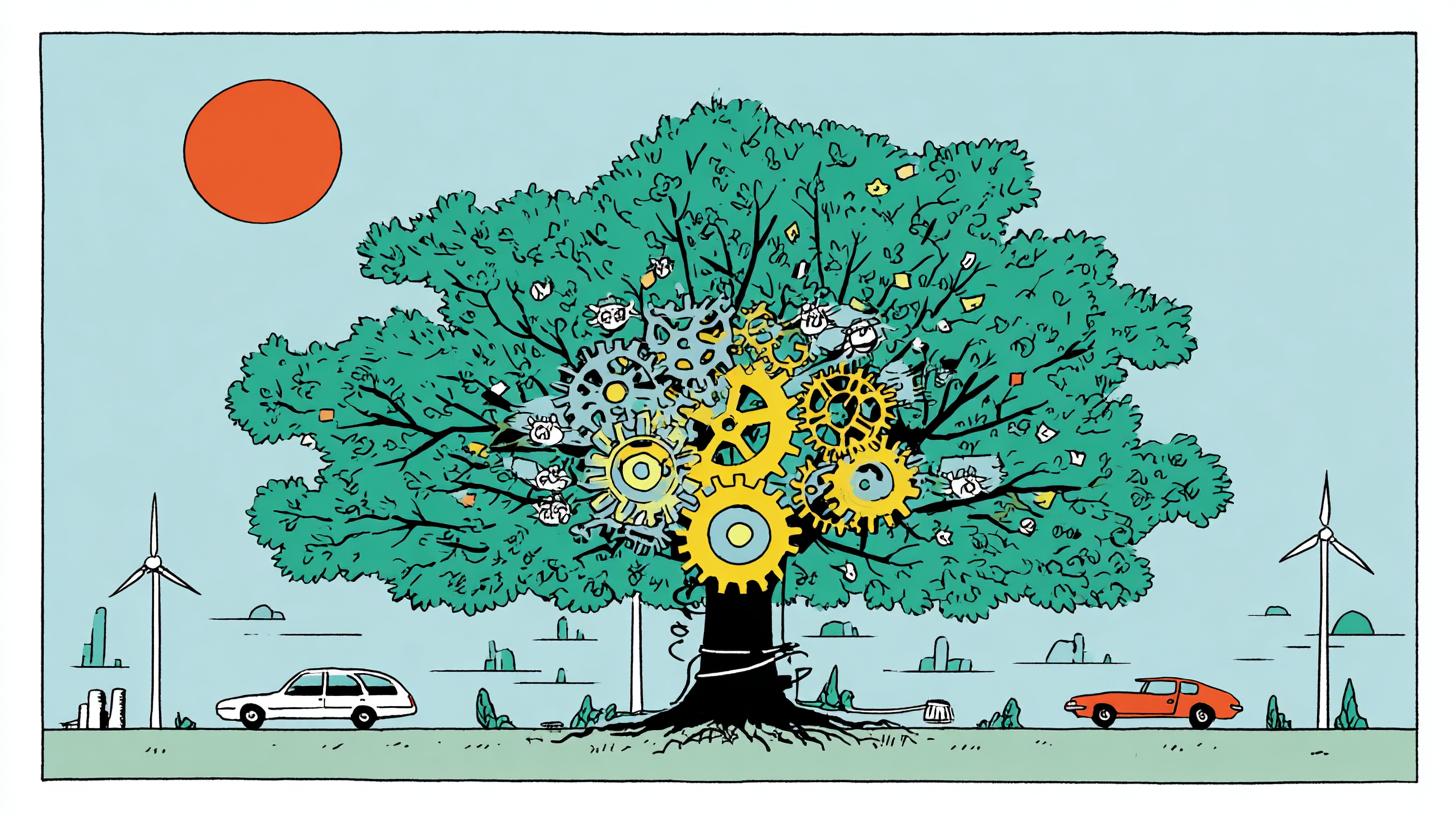

Now, the challenge is global warming. Once again, it won’t be inaction or anti-capitalist rhetoric that brings solutions, but rather the market’s own innovative force. We are already witnessing the emergence of competitive alternatives, such as ethanol and other biofuels, as well as the electric and hybrid car revolution. The world’s largest companies have invested billions in renewable energy, long-lasting batteries, and less-polluting production processes. This is, in essence, a natural process of adaptation: capitalism transforms challenges into opportunities.

This green market, in addition to mitigating environmental risks, opens the way for developing countries to become leaders in the new global economy. Brazil, for example, is one of the world’s largest sugarcane producers and can further expand its leadership in ethanol production, offering a competitive and clean energy alternative. Bolivia, with its vast lithium reserves, possesses a fundamental strategic resource for the manufacture of electric car batteries, offering the potential to position itself as a key player in the global energy transition. Chile and Argentina are also emerging in this sector, while African countries, rich in mineral resources and sunshine, can benefit from the growing demand for photovoltaic panels and inputs for sustainable technologies.

Rather than viewing the environmental agenda as an obstacle to growth, it should be seen as a strategic alliance for development. Sustainability, when integrated into market logic, does not restrict, but expands, the possibilities for the enrichment of nations. Through innovation and economic openness, poor countries can adapt to climate change and thrive, transforming themselves into global providers of sustainable solutions. Thus, combating global warming doesn’t have to mean stagnation; on the contrary, it can be a driver of a new stage of environmentally responsible economic growth.There is also a fundamental economic factor that is rarely mentioned: the so-called Kuznets Curve. This U-shaped concept was first used to describe how income inequality rises in early development but declines as societies grow wealthier. Economists have suggested that it can also be applied to the environment. Industrializing countries initially increase pollution as they prioritize jobs and growth, but as income rises, citizens demand quality of life, clean air, renewable energy, and sustainable cities. At higher levels of prosperity, technology and capital make cleaner production preferable.

Image Credit: Yorel Ktech, FEE

In other words, the best way for poor countries to reduce pollution is not to slow down their development, but to become richer. Economic growth creates the necessary tools to fund research, implement clean innovations, and meet growing social demands for sustainability. Prosperity and environmental protection are not opposing objectives, but complementary stages of the same evolutionary process.

This indicates that combating global warming involves not slowing growth, but accelerating it sustainably, enabling poor and developing countries to reach levels of prosperity that enable them to adopt clean technologies.

The post Wealth Is Green was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.