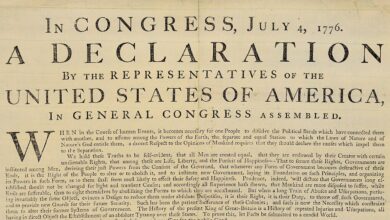

Morocco’s World Cup Gamble

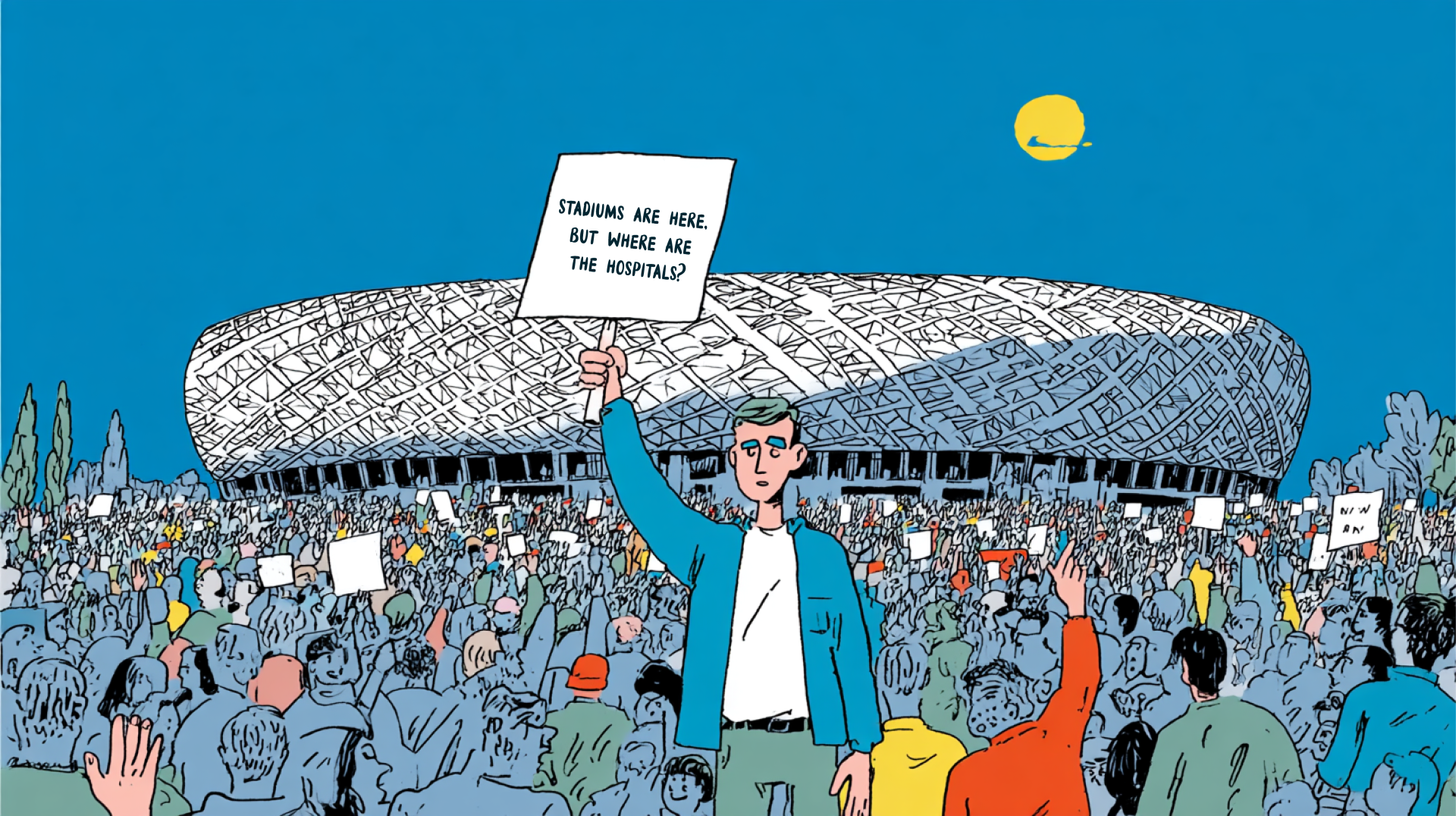

“Stadiums are here, but where are the hospitals?” The chant spread across TikTok and WhatsApp, and by the end of September, the Kingdom of Morocco saw its largest youth-led demonstrations in years.

Protesters in Rabat, Casablanca, and Marrakech clashed with police as resentment over billions in public funds for the 2025 Africa Cup of Nations and the 2030 World Cup (cohosted with Spain and Portugal) finally exploded. Young demonstrators accuse the government of channeling money into stadiums while hospitals and classrooms remain underfunded. A maternal death in Agadir, blamed on systemic healthcare failings, turned that anger into mobilization. Police arrested dozens, though most were later released.

Officials defend the projects as driving economic growth, citing job creation and infrastructure development. But the logic is revealing: authoritarian-leaning governments consistently prioritize prestige over welfare, with stadiums, airports, and mega-events that can be broadcast to the world. Meanwhile, the everyday needs of citizens (hospitals, schools, affordable housing) lack spectacle and thus political payoff.

Morocco’s young are now contesting this imbalance directly, and their protests capture a broader truth about autocratic governance: public money is often appropriated for the visible, not the vital.

The pattern is global. Russia’s Sochi Olympics became a monument to waste even as regional healthcare collapsed. Brazil’s World Cup left behind little but white-elephant stadiums while teachers were on strike for better pay. Qatar built glistening arenas at immense human cost—even leading to accusations of slavery—but the spectacle mattered more than dignity. Morocco’s gamble is similar: betting that the glow of the World Cup will outweigh the frustration of a generation.

Yet Morocco’s history suggests caution. The February 20 Movement in 2011, part of the Arab Spring, demanded reform and dignity. The monarchy conceded just enough—constitutional revisions, early elections—to ease pressure while preserving its authority and maintaining the constitutional status-quo.

Later, the Hirak al-Rif protests in 2016–2018, sparked by the death of a fishmonger in Al Hoceima, were met with mass arrests and long sentences condemned by Amnesty International. A 2022 Human Rights Watch report described a “playbook” of repression, such as smears, unfair trials, and pressure on families, that still defines Morocco’s response to dissent.

What is different today is the movement’s form. Organized under banners like “Gen Z 212”—the name taken from Morocco’s dialing code +212, and self-described as “a new wave of activism in Morocco, driven by young people demanding change”—and “Morocco Youth Voices,” it is decentralized, digital, and leaderless. Arrests, usually a tool of restraining leaders and silencing voices, cannot decapitate it; mainstream parties, seen as “inside the system,” are unable to co-opt the movement, and cannot neutralize it or wield it for their own gain.

This resembles the dynamic that fueled the Arab Spring, especially in Tunisia. There, the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in 2010 spread through Facebook and Twitter, galvanizing leaderless networks into a coalition that spurred a revolution. Autocratic regimes, used to dismantling hierarchies, found it far harder to contain decentralized swarms of outrage. Tunisia’s democratic experiment has since faltered, and similar explosions of outrage that spread across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), like that in Egypt, have ended in failure. Even so, the lesson endures: social-media-powered protests can destabilize even entrenched regimes.

Morocco’s monarchy knows this history. It must decide whether to risk heavy-handed repression, calibrated concessions, or a mix of both. Prosecutors could escalate charges under laws against “unlawful assembly” or “insulting officials,” chilling further mobilization.

The protests could dissipate if the organizers—what few there are—cannot sustain momentum beyond the weekends. Or the palace could blunt discontent by announcing visible social spending alongside stadium projects, reframing the narrative from prestige to balance.

But at heart, this is more than a tactical question. It is about the structural logic of authoritarian governance. Autocracies favor spectacle because it legitimizes them internationally and symbolically at home. To demand that public money be spent on schools and hospitals instead is to challenge that very logic. That is why Morocco’s youth, even without calling for regime change, are posing a radical challenge.

The palace can hope the protests fizzle, as they have before. But a generation raised in the shadow of 2011, digitally networked and globally aware, may not be so easily pacified. If Morocco continues to build stadiums while neglecting hospitals, it risks discovering that its World Cup legacy is not glory, but discontent.

And the lesson from Tunisia is simple: decentralized, leaderless protests can outlast repression, and once unleashed, they are far harder to control than rulers imagine.

The post Morocco’s World Cup Gamble was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.