The Spirit of a Pioneering Pilot

The best-known female aviator (“aviatrix” in the parlance of bygone years) is undoubtedly Amelia Earhart. A record-setting pilot and the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, she is assumed to have died in 1937 in the Pacific while attempting to circumnavigate the globe.

But before Amelia Earhart, there was Neta Snook, who taught Earhart how to fly. And before Snook there was Bessie Coleman, the world’s first black woman and first Native American to earn a pilot’s license. See more on Snook and Coleman in the suggested readings below.

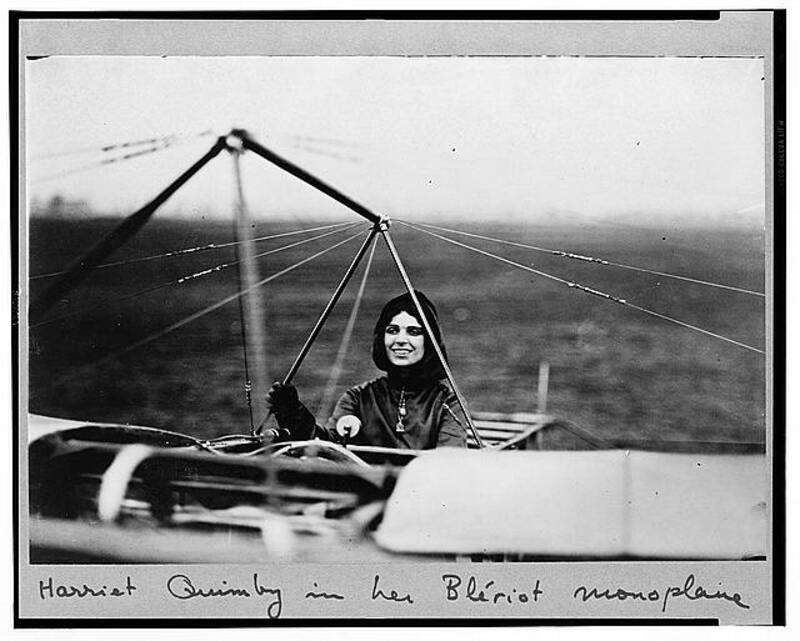

And before those three women, there was Michigan-born Harriet Quimby. One hundred and fourteen years ago today—on August 1, 1911—she made history. It was not yet eight years after the Wright Brothers flew for the first time.

A fountain in Burbank, California, serves as a shrine to Quimby. The fountain’s plaque reads as follows:

Harriet Quimby became the first licensed female pilot in America on August 1, 1911. On April 16, 1912, she was the first woman to fly a plane across the English Channel. She pointed the direction for future women pilots including her friend, Matilde Moisant, buried at the Portal of the Folded Wings. The number of licensed female pilots increased to 200 total by 1930 and between 700 to 800 by 1935.

In the same month that journalist Quimby earned her pilot’s license, she authored an article in Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly titled “The Dangers of Flying and How to Avoid Them.” She wrote:

Every new invention of note has to go through its own trying experience. Some would not ride on the first steamboat because they were sure the boiler would explode. Some bitterly opposed the construction of the first railroad because they said it would be deadly to run trains at full speed. Some old farmers insisted that it would be impossible for them to keep cows off the tracks and were serious about it.

Quimby went on to point out that the fears accompanying those new inventions proved largely unfounded. By the time she was writing, and despite a few accidents, people in great numbers and safety were riding on steamboats and railroads.

Further along in her article, she wrote some lines that a few months later seemed hauntingly prophetic:

The fatalities of the air come so quickly and unexpectedly and the end is so sudden that the cause of the catastrophe is obviously left to surmise, so we have as many causes as there may be conjectures. None of them may be right. The aviator who falls a thousand feet or more rarely survives to tell of his misfortune.

On July 1, 1912, Quimby participated in an aviation contest in Massachusetts. Riding with her was the event organizer, a man named William A. P. Willard. Suddenly and for some reason never discovered, the plane pitched violently. Both Quimby and Willard were ejected. They fell to their deaths from an altitude of a thousand feet, the very height she referenced in her article the year before. Quimby was just 37 years old.

Some might say Harriet Quimby should never have left the ground. Flying in planes less than a decade since their invention was immensely dangerous. Why take risks you don’t have to?

Harriet Quimby knew that flight was a risky endeavor. She even wrote about that fact but pursued her dream anyway. That is precisely the spirit that animates every worthwhile journey into the unknown. I don’t know about you, but I am profoundly grateful for it. If every human craved safety over uncertainty, we might never have ventured forth from the cave.

From what I’ve learned of Harriet Quimby, she was a fearless never-quitter. Indeed, Fearless is in the title of a biography of her. I think she would love the following lines from the popular American poet Edgar Guest, titled “Don’t Quit”:

When things go wrong, as they sometimes will, when the road you’re trudging seems all uphill;

When the funds are low and the debts are high, and you want to smile but you have to sigh;

When care is pressing you down a bit—rest if you must, but don’t you quit.

Life is queer with its twists and turns, as everyone of us sometimes learns. And many a fellow turns about when he might have won had he stuck it out.

Don’t give up though the pace seems slow. You may succeed with another blow.

Often the goal is nearer than it seems to a faint and faltering man; often the struggler has given up when he might have captured the victor’s cup; and he learned too late when the night came down, how close he was to the golden crown.

Success is failure turned inside out—the silver tint of the clouds of doubt. And when you never can tell how close you are, it may be near when it seems afar.

So stick to the fight when you’re hardest hit—it’s when things seem worst, you must not quit.

Additional Reading

The Uncommon Life of Bessie Coleman by Lawrence W. Reed

Neta Snook: The Woman Who Taught Amelia Earhart How to Fly by Lawrence W. Reed

Lessons from the First Airplane by Lawrence W. Reed

The Glamorous, Adrenaline-Fueled Life of Harriet Quimby by Katrina Gulliver

The Dangers of Flying and How to Avoid Them by Harriet Quimby

Edgar Guest: Remembering the People’s Poet by Lawrence W. Reed

Fearless: Harriet Quimby, A Life Without Limit by Don Dahler

Harriet Quimby: Flying Fair Lady by Leslie Kerr

The post The Spirit of a Pioneering Pilot was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.