It’s a Test to the Institutions

For the first time in years, we are witnessing multiple flashpoints, where the world would have looked to international organizations like the United Nations for clarity. However, what we see now are authoritarian leaders, testing the system’s limits. How far can they push? What consequences, if any, will they actually face?

It starts with politically misaligned regimes eager to test the will of “The West.” They push buttons to see the reaction. One such case: Nicaragua’s recent and voluntary decision to withdraw from UNESCO. On the surface, it seems inconsequential, since UNESCO is barely relevant, but in reality, it signals something deeper about the erosion of our international institutional framework.

The Original Mission

First things first—beyond the specific roles of individual UN agencies, the original purpose behind the creation of these institutions was ambitious and yet vague: “to maintain international peace and security.” The ambiguity left room for wild interpretations. Somewhere along the way, the mission blurred. It’s as if no one was there to ground the conversation in a room full of wild ideas. Or maybe, there were voices of reason, but they weren’t convincing enough. Either way, the result is clear: institutional drift, that comes with consequences.

What are the costs of abandoning a structure that, for better or worse, has helped prevent another Great War? Even if the League of Nations failed to stop World War II, and the absence of global conflict can be credited to nuclear deterrence and NATO’s military umbrella, the postwar institutional order played a role in offering a space for rules-based diplomacy.

This is where the debate shifts to the question of institutional evolution—or as some might argue, involution—of the institutional framework that gave birth to entities like the UN. What do nations actually gain from staying in the club? And what happens when the club evolves, or worse, when it decays?

Decay isn’t just a matter of irrelevance or inefficiency; it’s about credibility. The very institutions tasked with safeguarding norms and values have, in some cases, violated them. Examples include UNICEF’s reported cases of sexual exploitation in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Human Rights Watch’s report of abuses in Haiti. Corruption and abuse have chipped away the UN’s legitimacy, as have the repeated failures of UN peacekeeping missions that signal little fear to despots from intervention. So why remain in a system that fails to hold itself accountable?

And What Are the Implications of Simply Walking Away?

Membership once came with tangible benefits: preferential access to trade, fewer barriers, and stronger diplomatic relationships. More trade typically means more ties, and more ties (at least in theory) mean fewer conflicts. There was now interdependence and mechanisms for solving conflict, but what happens when they stop working? When wars still erupt, trade disputes become regular, and complaints get buried in paperwork? And most importantly: what does it mean when even the architect of the postwar order—the United States—is no longer as committed to those founding rules? Meanwhile, rising powers like China are building alternative international networks of loyal client states and regional blocs (like the Belt and Road Initiative). These affiliations may soon rival or surpass the UN in relevance and appeal to authoritarian regimes.

Back when the postwar world order was built, the terms were clear: join the club, follow these rules, and be rewarded. Defy them, and face the consequences. It was a membership with privileges, and leaving had real costs. Being expelled was seen as a major diplomatic punishment, and newly independent nations campaigned for years to become members. Countries complied because the stakes were high. Many still believe those costs remain, which is why they hang on. But some, like Nicaragua, and perhaps more to come, have realized they can just walk away. And quite frankly, the global reaction has been muted…

Nicaragua’s Tyranny

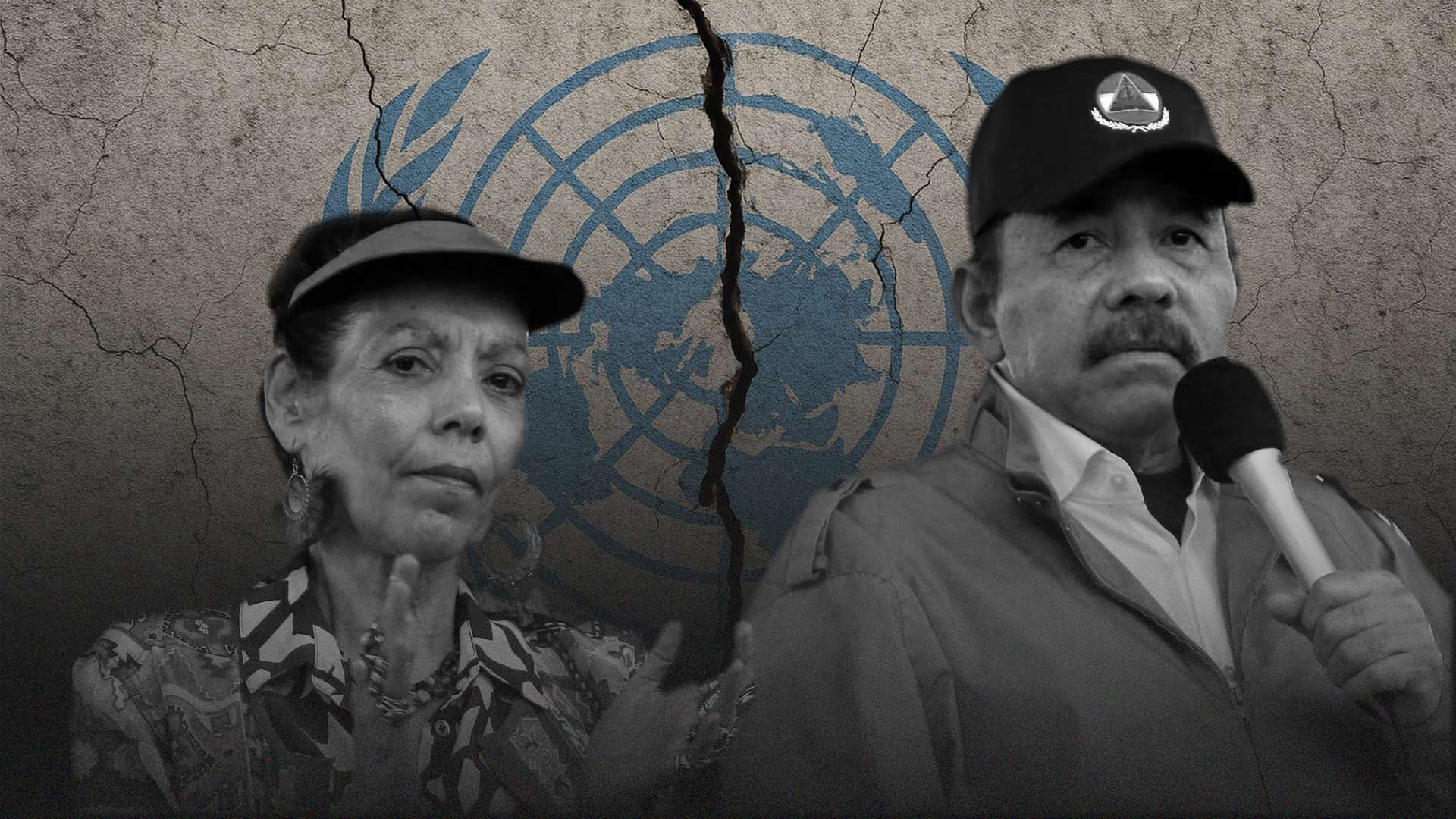

Star-crossed co-tyrants (and spouses) Rosario Murillo and Daniel Ortega have spent nearly two decades consolidating power. Their political saga didn’t begin with their 2007 return to office; it goes back further. Ortega first led Nicaragua in the 1980s as head of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), after overthrowing the Somoza dictatorship. A bloody civil war, US-funded Contra insurgency, and eventual electoral defeat in 1990 followed. But Ortega was planning longer-term: he returned, this time with Murillo, his wife, by his side. I wrote more about this context back in 2022.

This makes Nicaragua the third-longest-standing tyranny in power on this side of the globe, with 17 years compared to Cuba’s 66 and Venezuela’s 27.

Earlier this year, a constitutional reform allowed Nicaragua to become the first country in the modern political world with co-leadership, or, in scientific terms, “formalized dual executive.” Technically, a vice president still exists on paper, but the position remains vacant. Don’t rush to submit your CV, though, because it does not seem like they are hiring.

What followed was internal abuse, and in the international arena, a deliberate withdrawal from international bodies: IOM, ILO, UNESCO, FAO, and even the UN Human Rights Council. Over just five months, Ortega and Murillo have severed Nicaragua’s ties with institutions that once offered oversight, sending a clear message: “We no longer need the club.” Instead, they’re leaning toward alternative networks, those aligned with China, that offer resources and recognition without the burden of accountability.

So, who speaks for Nicaraguans now? Who advocates for its citizens? This situation challenges the fitness of international institutions. Are they truly equipped for the challenges and complexities of today’s geopolitical crises, or are they mid-20th-century relics trying to solve 21st-century problems?

Institutional… Design?

Policymakers usually argue that “the problem is design”—institutional design. Perhaps. But maybe it’s time to revisit Hayek’s Fatal Conceit and his warning about arrogance, the belief that we can engineer political solutions to complex human realities. It was naïve to think these institutions would last forever without adaptation.

This isn’t to say the global order is destined to collapse and that World War III is around the corner. But institutions, like nature, must adapt or die. And that adaptation requires restoring credibility, relevance, and, most importantly, trust.

The real question isn’t whether these institutions can evolve. It’s how. While international leaders deliberate in their headquarters, tyrants are acting. And by the time the club reacts, it may be too late.

Will they act in time?

The post It’s a Test to the Institutions was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.