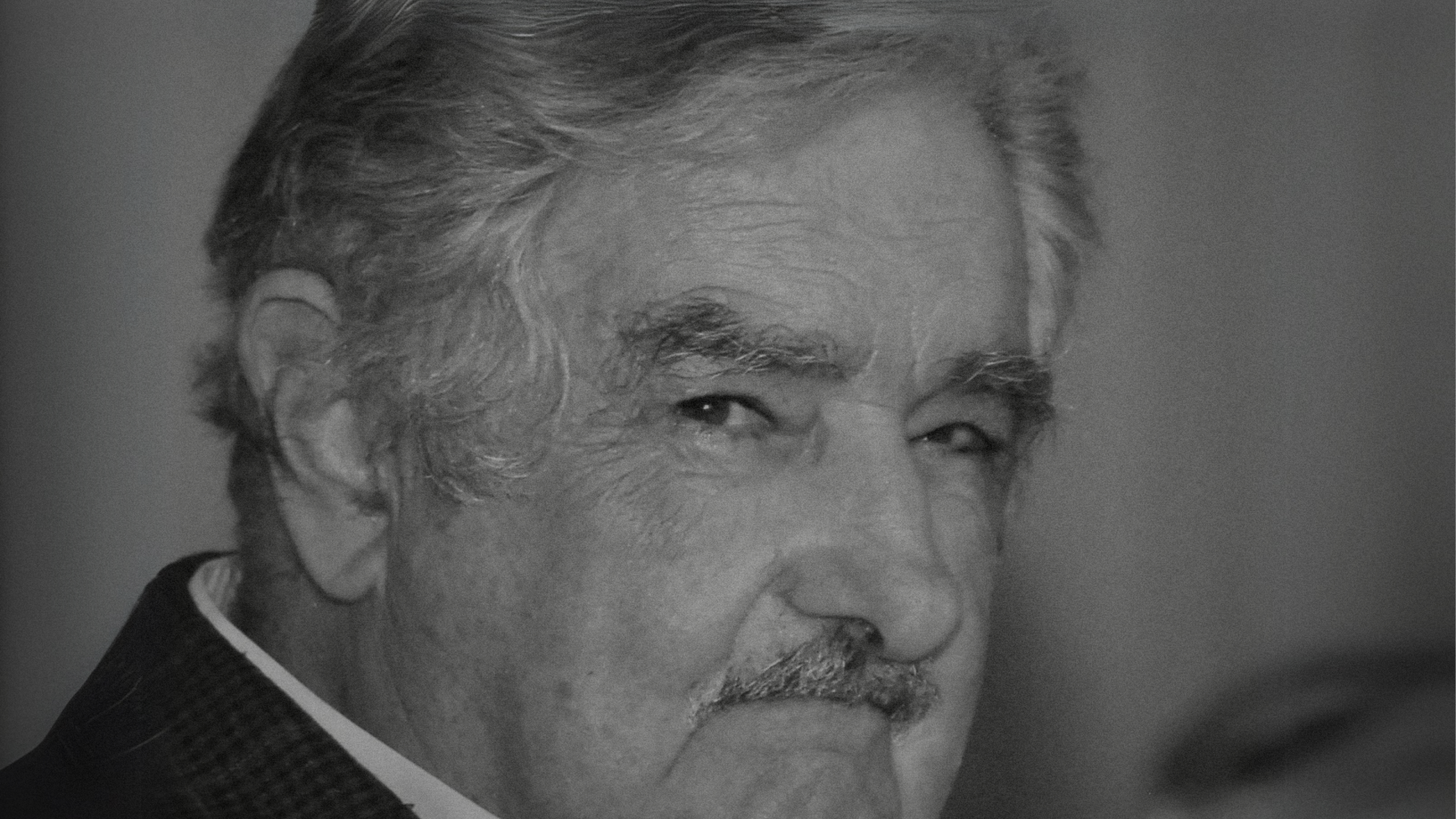

El Pepe

José Mujica, Uruguay’s guerrilla-turned-president-turned-political-popstar, passed away on May 13. Trying to explain him to anyone living outside Uruguay can be a challenge, because Mujica was a completely Uruguayan character.

Let me illustrate. Uruguay is a country with two souls. One, urban, middle-class, socialist, with mostly European descent, and cosmopolitan pretentions that are impossible to fulfill in a country of 3 million people on the outskirts of Latin America. That’s mostly the capital, Montevideo, where half of the population lives. The other half lives in what is generally called “the countryside,” though the bulk of it resides in small towns scattered in a territory smaller than South Dakota. And its people, though ethnically similar, have a very different approach to life and politics. They are more individualistic, suspicious of government reach, linked to extensive farming production, and tend to vote conservative options. Comparisons to Texas have been made.

Mujica was a very peculiar, and some would say fabricated, mix of these two worlds. Worlds that since the country’s birth have clashed relentlessly, in a political power struggle that involved outright civil war throughout the 19th century. After that, the struggle “civilized” mostly, and the country had a period of economic flourishing that created the most equal and democratic society on the continent. Until Mujica and his friends, dazzled by the Cuban Revolution and frustrated by a period of economic stagnation, launched a guerrilla uprising that ended with them in prison for a decade, and the country in a military dictatorship.

After his release from prison, pardoned by a law passed by the same political enemies he had fought a decade before, Mujica starred in one of the most amazing—and some would say Hollywood-worthy—redemption stories in continental politics. He was the man that pushed his guerrilla group, the Tupamaros, to accept the rules of democracy, and eventually turned it into one of the most powerful political movements in the country, eventually making him president in 2010. That was made possible by a mix of charisma, straightforward talk with no concessions to political correctness or even politeness, and an extraordinary grassroots campaign. Mujica and his peers literally walked the whole country, gaining the trust of ordinary people, both in the city and in the countryside.

He made a point of showing that he lived the same way as every poor person in the country, and he effectively did so, even though his wife, Lucia Topolansky, a higher-ranked Tupamaro than himself, came from a very wealthy family. That was when the myth of “the world’s poorest president” started to gain traction. It all began during his first days as a congressman, when an unconfirmed episode repeated in bars and newsrooms, claimed that he arrived with his not-at-all-polished-look to the grand Parliament building on a battered Vespa, and parked in the spot reserved for elected representatives. A policeman approached him and asked how long he planned to stay there. And he supposedly replied: “The whole five years, unless something terrible happens.” The legend only grew as he scaled the political ladder. As president he was still living in a very humble house on a small farm outside Montevideo, where he would receive the king of Spain or Brazilian presidents, forcing them to sit on a chair made with plastic bottle caps.

His political legacy, as anyone reading this story can imagine, is extremely polarizing in Uruguay. Some love him; some hate him. Very few, though, dispute that his government was bad. Even though it happened at the same time as the biggest economic boom in the region, with export prices for Uruguayan products never before seen thanks to China’s expansion, he left the country with more debt than when he entered office. His time in power bankrupted the state-owned energy company that has a legal monopoly to sell gas, and never delivered on reforms he had promised as essential for the country’s future. In education, something that Mujica claimed was an absolute priority for his term, nothing happened.

On the other hand, during his government, abortion and same-sex marriage were legalized, and marijuana was regulated in a bizarre way, where the government holds a monopoly on production and selling. The truth is that Mujica never championed any of these reforms before his presidency, and only embarked on them after perceiving they had strong support from the young, intellectual left-leaning class, a group he generally despised.

That’s a perfect expression of Mr. Mujica’s political talent. He had a superhuman capacity to anticipate the trend changes in the electorate, and shamelessly change course from one minute to the next. He was also a cutthroat politician, and whoever mistook him for a nice grandpa figure would pay the price in full for his error.

He also contributed to a deep downgrade in political argumentation in Uruguay. In breaking every code of public speech and not hesitating in profane language, he triggered a degradation in a system once known for its politeness, even in the worst ideological battles. Not very far from what Donald Trump has been accused of in the US. Comparison between these two, apparently radically different characters, has not been unusual in Uruguay. Of course, more in the form than in the substance. Never in fashion or taste.

Mujica was a total political animal. Even during his final days, he got up from his bed to send a moving message to the voters in the last week of the November election. His hair messy, his teeth gone, and looking about to expire, he told them to vote for his political heir, Mr. Yamandú Orsi. And, according to most analysts, that was key for Orsi’s win.

He was contradictory, one day criticizing business leaders for being greedy, the next union bosses for being illiterate. He was an unrepentant socialist, but he could throw the most vitriolic criticism to communist experiments. He was a friend of Fidel Castro, but would get along just as well with the former king of Spain. Most of all, Mujica was a virtuoso, who could play better than anyone the subtle keys that move the regular Uruguayan emotions.

You could argue that he could have used that power for a better cause, or achieved better results. But in a world of aseptic, manufactured, and poll-obsessed politicians, he was one of a kind.

The post El Pepe was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.