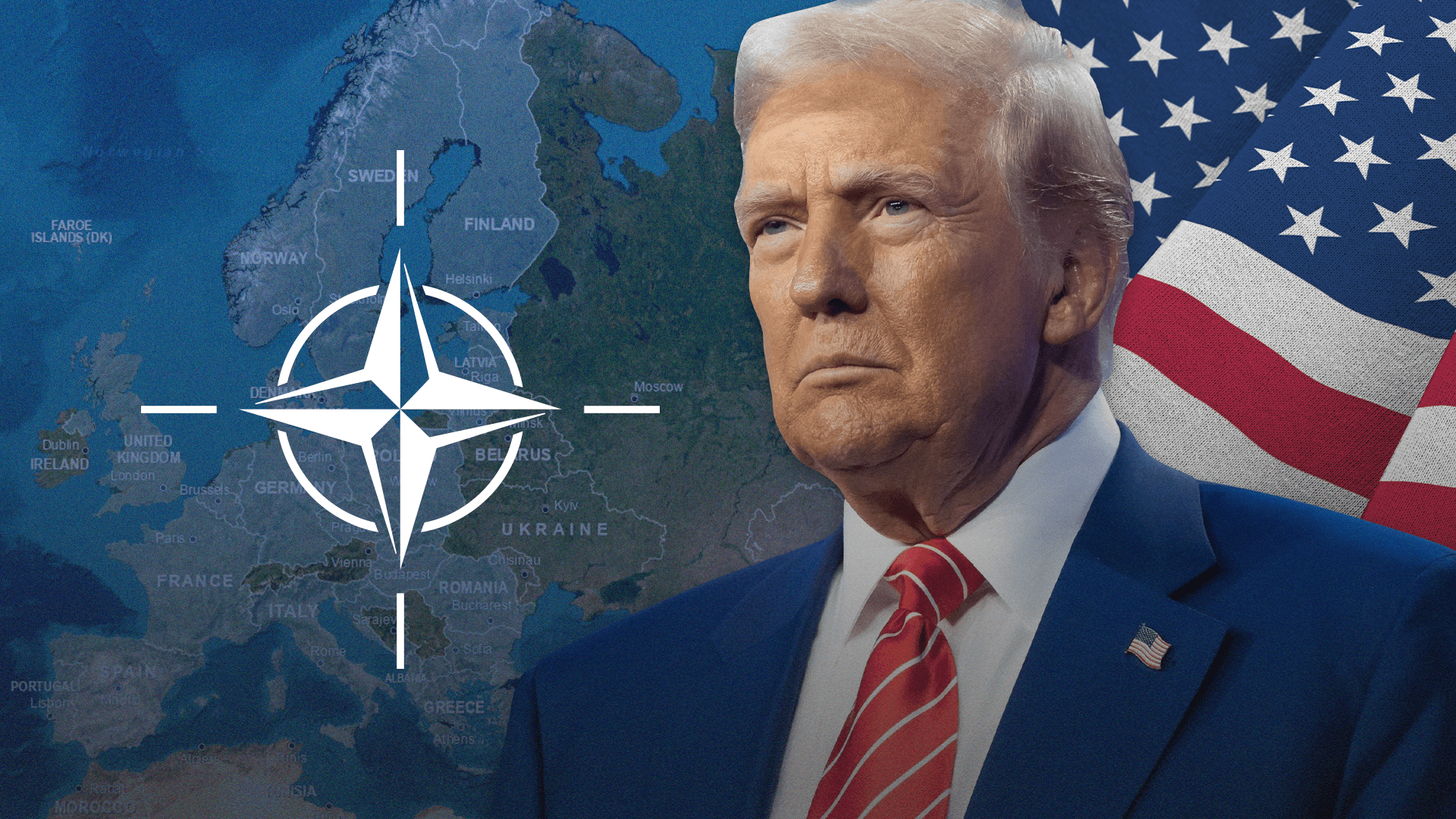

Not Happy With NATO

Two days after his inauguration on January 20, Donald Trump criticized Spain for its “very low” defense spending, while also confusing it with one of the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and five others). Spain currently ranks last amongst NATO’s 32 members in military expenditure: in 2024, it spent 1.38% of its GDP on defense, once again failing to meet the 2% target agreed upon by member states in 2014.

Reaching the 2% target will be difficult for Spain—but even that is not enough for Trump. A few days after singling out Madrid, he announced that NATO members should increase their defense expenditure to 5% of GDP. With this demand, Trump has aligned himself with NATO’s Secretary General Mark Rutte. Speaking in Brussels last December, Rutte said it was time to “turbo-charge our defense production and defense spending” to match Russian military expenditure, which is expected to account for more than 6% of GDP this year. Europe, argued Rutte, must return to a Cold War mentality.

Spain joined NATO in 1982, seven years after Francisco Franco’s forty-year dictatorship ended. It voted to remain in the alliance in 1986, the same year that it joined the EU, but didn’t become part of the integrated military structure until 1999. Spain has always been a low defense spender, in part due to its location on the westernmost edge of Europe, over 2,000 miles (3,200 kilometers) from Moscow. Other factors include the prioritization of investment in the welfare state, public opposition to military spending, and, since 2015, a fractured political scene in which budgets have become highly contentious. Spain has also historically relied on the US: as a former Spanish ambassador to NATO recently said, “We grew accustomed after the Second World War to delegate our ultimate defense to the US through its military umbrella.”

Trump believes that this relationship has become one-sided. “We have a thing called the ocean between us, right?” the incoming US president said in January: “Why are we in for billions and billions of dollars more money than Europe?” His hope is that, by meeting the new spending target, Europe will narrow the gap that currently separates it from the US. Last year, the US accounted for 68% of NATO spending, whereas European members (including the six non-EU-affiliated nations) contributed 28%. Europe and Canada did, however, boost their NATO defense spending by 20% in 2024.

Spain’s Socialist prime minister Pedro Sánchez responded to Trump’s criticism by saying that the country is on track to meet the 2% spending target by 2029 and that it has doubled its defense expenditure since 2018. But Sánchez faces strong opposition from his left-wing allies. Last April, Iñigo Errejón, then spokesperson for the leftist alliance Sumar, which makes up half of Spain’s Socialist-led coalition, called on the prime minister to cut diplomatic ties with Israel and retract his commitment to increasing defense spending. Spain, he said, “should not make any sacrifices to fatten the military industry or the war economy.” The Spanish left, it seems, is very far from adopting a Cold War mindset.

Leftist Podemos took a similar stance on military aid to Ukraine, following Russia’s invasion in February 2022. As the war approached its first anniversary, Sánchez announced the deployment of six Leopard tanks to Kyiv—a decision that exposed fundamental disagreements in the leftist coalition. Podemos, at the time the Socialists’ junior partner, opposed what it called the “NATO war rage” and refused to “escalate the war in Ukraine with more and more weapons to encourage the warlords.”

So far, Sánchez has ignored Sumar’s objections, further weakening an already fragile partnership. When he agreed on a new arms shipment to Ukraine with Volodymyr Zelensky in May last year, including anti-aircraft missiles, ammunition, and 19 more Leopard tanks, Sumar reacted angrily, claiming that the decision had been made in secret. Yet Sánchez at least had the popular opinion on his side: a poll conducted at the time revealed that 80% of Spaniards supported sending military aid to Ukraine—although according to a different survey two months later, 51% opposed increased military expenditure in general. That poll also found that 47% of Spaniards thought the government was concentrating on Ukraine too much and not enough on domestic matters.

Spanish Defense Minister Margarita Robles responded to Trump by arguing that a country’s commitment to security should not be measured by its military investment. Currently, 3,743 members of the Spanish armed forces are deployed in 15 countries, which include: 2,450 on NATO missions, 671 on UN missions, and 324 on EU missions. Spain’s deployment of 183 military personnel in Iraq makes it the largest contributor to the country’s NATO mission, which has been under Spanish command since May 2023. Robles insists that Spain remains “a serious, trustworthy, responsible, and committed ally” of NATO.

Trump’s criticism of the EU for not pulling its weight in NATO spending raises the question of whether the 5% goal is even feasible. Poland, which spent 4.12% of its GDP on defense last year, comes closest. Italian Defense Minister Guido Crosetto has said that 5% would be “impossible for almost all the nations in the world.” Italy, historically one of the EU’s weakest economies, is in a similar position to Spain: it’s planning to spend 1.57% of GDP on defense this year and is not expected to reach 2% for another three years.

Yet the governments of Sweden, Estonia, Germany, and the Czech Republic support the idea of increased defense spending. This divided response highlights the problem with blanket targets, another example being the EU’s 3% budgetary deficit goal (which Spain has also frequently missed). Such targets are more suitable—or more necessary—for some countries than others. Apart from Poland and the US, the two NATO nations that spend the most on defense are Estonia (3.4%) and Latvia (3.1%), both of which share a border with Russia. Their Baltic neighbor Lithuania, ranked sixth in NATO for military expenditure, was the first country in the alliance to back Trump’s proposal of a 5% spending goal.

Trump’s call for increased spending from NATO’s European allies is fully in line with his plan to slash domestic expenditure, including the Pentagon’s $800 billion budget. But he has underestimated the role that geopolitics, economic health, and public sentiment play in shaping defense budgets. All of those factors will make it difficult for Spain to hit the 2% goal, let alone one more than twice as high. The Spanish government also faces internal challenges, on which the extra funds would arguably be better spent—such as high unemployment (especially amongst young people), a housing shortage, and an immigration crisis. Spain, as a NATO ally, is unlikely to earn Trump’s praise anytime soon.

The post Not Happy With NATO was first published by the Foundation for Economic Education, and is republished here with permission. Please support their efforts.